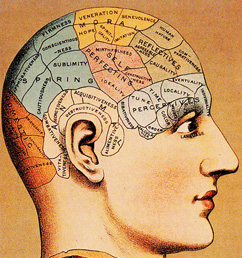

Parker Palmer, in a beautiful and important essay called "The Broken-Open Heart: Living with Faith and Hope in the Tragic Gap," speaks of our need to overcome "the primitive brain":

Parker Palmer, in a beautiful and important essay called "The Broken-Open Heart: Living with Faith and Hope in the Tragic Gap," speaks of our need to overcome "the primitive brain":

No one who aspires to become fully human can let the primitive brain have its way, least of all Christians who aspire to a gospel way of life. When the primitive brain dominates, Christianity goes over to the dark side. Churches self-destruct over doctrinal differences, forgetting that their first calling is to love one another. Parishioners flock to preachers who see the anti-Christ in people who do not believe as they do. Christian voters support politicians who use God's name to justify ignoble and often violent agendas. When the primitive brain is in charge, humility, compassion, forgiveness, and the vision of a beloved community do not stand a chance.

This primitive brain, he explains, snaps us into the fight-or-flight reflex. That reflexive reaction to danger has great survival value when you're trying to escape from a saber-toothed tiger or when you are trying to bring down a mastodon to feed your clan. But the primitive brain isn't so helpful when you're in the middle of a tense conflict with your spouse, or you're negotiating with a high-strung teenager.

Or dealing with terrorists.

Terrorism, contrary to what our political leaders sometimes tell us, isn't insane. It's actually a demonically brilliant strategy of manipulating an opponent to react from the primitive brain. Terrorists aren't stupid; they know that by tempting us to submit to the primitive brain, we will become stupid and easy to manipulate. More specifically, if your enemies know they can provoke you to fight or flee on their prompting, they can pull your chain and push your buttons so you will overextend, overspend, and over-react.

By tempting you to overextend again and again, little by little they cause you to exhaust yourself and render yourself more vulnerable than you would have ever been through one big, obvious direct attack. By leading you to overspend again and again, little by little they render you increasingly vulnerable to economic indebtedness, recession, depression, collapse, and all the civil unrest that accompany them, further weakening you from within. And by prompting you to overreact again and again, they know that little by little you will gamble away your moral authority, lose the respect of other nations, drive away your friends, and earn more enemies. And when the primitive brain dominates, it won't be long until you're turning on each other.

If this sounds familiar, then perhaps we're waking up to see how we have been dancing to the fearful song of the primitive brain, marching to the drumbeat of reactivity, and playing stupid to the script terrorism. And perhaps we begin to see the ancient wisdom of Jesus' words: those who live by the sword die by the sword, because sword-play submits you to the primitive brain.

Immediately for me, more language from the New Testament comes to mind. What would it mean, in this context, to be transformed by the renewing of our minds? What is the primitive brain but what Paul called "the flesh" -- and what liberates us from it but the Spirit? What would it mean to "let this mind be in us that was in Christ Jesus?" What would it mean to put primitive ways behind us, and mature from the primitive brain's fear-driven reacting to the "more excellent way" of love-inspired living? What would happen if we stopped listening to the religious leaders who play to fear and instead began listening to those who lead us to higher ground?

The challenge isn't easy. As Palmer says, "Unfortunately, the fight or flight reflex runs so deep that resisting it is like trying to keep your foot from jumping when the doctor taps your patellar tendon." But we can learn to deal with danger and tension more creatively, he affirms, through learning new ways of using language, through the arts, through education, but especially through our faith communities. Misguided religious leaders, of course, embed people ever more deeply in the primitive brain simply by wallpapering it with religious language. But wise religious leaders help people learn to open hearts and hands that have been clenched tight in fear.

Palmer challenges his fellow Christians, but the challenge could easily be adapted to people of all faiths: "If we Christians want to contribute to the healing of the world's wounds rather than to the next round of wounding -- and we have a long history of doing both -- much depends on how we understand and inhabit the cruciform way of life that lies at the heart of our tradition." We who follow a crucified Lord should not be the last to discover the power of unarmed love and vulnerable forgiveness to liberate us from the primitive reactions of fear, fight, and flight.

President Roosevelt may have overstated the case when he said we have nothing to fear but fear itself, but he was conveying the truth that with every external threat comes a more subtle threat from within: we yield to the primitive brain and become puppets on the strings of fear. As dangerous as any single act of terrorism may be, our reactions to it are no less dangerous. So here's the question: can the fear of fear challenge us to rise above fear? Or will the fear of danger keep us stuck in the primitive brain?

P.S. If you're a Christian who fears Muslims -- or who knows others who do -- a good first step in addressing fear would be to sign up for the Why Do You Fear Me? webcast coming up Jan. 28.

Brian McLaren is an author and speaker whose next book A New Kind of Christianity: Ten Questions That Are Transforming the Faith

Brian McLaren is an author and speaker whose next book A New Kind of Christianity: Ten Questions That Are Transforming the Faith.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!