“It so happened,” wrote Michele de Piazza, a member of the Franciscan order from Sicily,

that in the month of October in the year of our Lord 1347, around the first of that month, twelve Genoese galleys, fleeing our Lord’s wrath which came down upon them for their misdeeds, put in at the port of Messina. They brought with them a plague that they carried with them down to the marrow of their bones, so that if anyone so much as spoke to them, he was infected with a mortal sickness which brought on an immediate death that he could in no way avoid.

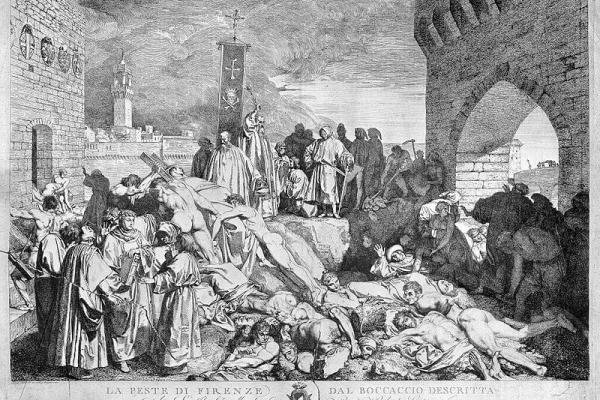

La moria grandissima (the great mortality), an outbreak of bubonic and pneumonic plague that moderns call the black death, appeared to almost everyone in Europe as a pouring out of the wrath of God upon sinful humanity. Some Christians, particularly those whose job it was to tend to the ill and infirm, responded by sticking to their posts and loving their neighbors as themselves in full awareness that the consequences might be fatal. We also know that some engaged in scapegoating and blamed the Jews for the plague, and the effects of their shameful actions have reverberated even into modern times.

Most people did something in between. They neither engaged in violence nor stepped out in love and obedience toward those beyond their immediate circle. They avoided sins of commission but slid naturally into sins of omission against their neighbors — and these actions too had lasting effects.

Between the years of 1347 and 1352 at least a third of the population — and in some regions, 60 percent or more — died terrible deaths. First came the fever, headaches, chills, and sudden weakness, then a swelling and pain in the lymph nodes or a terrible, bloody cough that rapidly turned to pneumonia. Others went into septic shock and passed almost immediately. One Sienese man put to paper what could hardly have been an uncommon thought in those days: “This is the end of the world.” As many as 50 million people would die by the time the plague finally subsided.

Accusations and fear of the other

The disease was spread by the bacteria yersinia pestis originally through rat or perhaps marmot flea bites, but, medieval medicine being what it was, no one could have known that. Instead, they thought that infected air or, occasionally, demons or other malevolent forces were at work.

Unfortunately, many came to believe those malevolent forces were the local Jews. Anti-Semitism had arisen periodically in Europe before the plague, and the local population had grown resentful of Jewish moneylenders since Christians could not charge interest. But in Germany, Northern Italy, and the Langue d’Oil and Langue d’Oc regions of France, a rumor began to circulate in the first months of the plague that Jews had poisoned the well water and caused the sickness. In several places, Jews were rounded up, beaten, and murdered. Some were arrested and tortured into false confessions, which then set off another round of pogroms. An old story that Jews kidnap and sacrifice Christian children during Passover has its roots in the instability of these times. So does the conspiracy theory of an international Jewish cabal planning world domination, a version of which became the Judeo-Bolshevik myth that led Hitler to invade the Soviet Union.

Tragically, one of the period’s most well-known Christian reformist groups was among the worst persecutors of the Jews. The Flagellants originated in Germany, but their violent anticlericalism and disturbing masochism quickly made them famous enough to gain a following in France and Italy. They took 33-day pilgrimages on which they whipped themselves three times per day, and crowds would often gather to take in the spectacle. Sometimes they would harass or attack Jews who had not succeeded in hiding themselves.

In the late spring of 1349, after the populace had endured more than a year of the plague, the Flagellants began one of the worst periods of anti-Semitic persecution before the Holocaust. “Flagellant columns killed Jews wherever they found them,” John Kelly writes in The Great Mortality, “including in Frankfurt, where the arrival of a troupe of marchers inspired one of the bloodiest pogroms of the mortality. The local Jewish quarter was sacked, its inhabitants killed, and their goods stolen.”

Pope Clement VI did what he could to stop the violence, even asserting that those who engaged in it had been deceived by Satan. It’s impossible, Clement wrote in a papal bull, that the Jews were at fault for the plague. How could they be? It “afflicts the Jews themselves.” But too few had ears to hear. The violence continued.

Perhaps it’s not surprising that Clement’s remonstrations went unheard. The man had lived opulently for years surrounded by great need. Popes had resided in Avignon since a French powerplay moved the papacy there in 1309, and Clement, the fourth pope under the French thumb, wanted a court that could rival the greatest in Europe. He built a new palace, became an extraordinary patron of the arts, and had paid musicians around him at all times. Odds are that he was also no stranger to the more poignant pleasures of the flesh. All the while, famines and other crises had much of Avignon, not to mention the rest of Europe, struggling simply to hold body and soul together.

A pope flees while others tend to the sick

The prestige of the papacy had suffered for these reasons and others even before people began falling ill, but it may have taken another blow when, at the very height of the plague, Clement fled Avignon in May of 1348. Leaving may or may not have been the right thing to do given the circumstances. Phillip Ziegler estimates that Avignon lost fifty percent of its population, and if the pope too ended up among the dead, it would have only discouraged an already weary people. Many commoners were fleeing too, and few were surprised at Clement’s decision. But Avignon’s citizens already felt acutely their destitution — and, one might conjecture, their abandonment — whenever they looked up at Clement’s gigantic, empty residence. Despair at his departure would have been understandable.

In some places, thankfully, the church did not forsake those suffering. The sisters of the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris, the oldest hospital in the world, embodied the love of Christ by being obedient to their calling even to the point of death, doggedly tending to the sick even as they themselves were felled by the disease. Parish priests too typically stuck by their people. Not surprisingly, the plague killed priests at a far higher rate than the general population, and many displayed extraordinary courage in staying to administer last rites to the dying, especially since they had to know they too would likely be infected.

But there were men of the cloth who apparently lacked the mettle — or, perhaps, the faith —required in these difficult months. Some historians believe that the behavior of priests during the plague led to a further diminishment in the standing of the church afterwards. Many stayed at their posts but, held captive by their own terror, avoided as much risk as they could even when obedience to Christ required it of them. In taking such a course, they did not manage to lead their people to trust in God. And then, of course, there were a few plague-stricken communities who woke up one morning to find that their priest had snuck away, abandoning them in their darkest hour.

“It would be unfair to heap obloquy on Clement,” John Kelly wrote of the pope. “[I]f he can be accused of anything, it is the sin of being ordinary in an extraordinary time.” It seems the same could be said of many priests as well, and their ordinariness — or, one might venture, faithlessness — bred ordinariness among their people in the years that followed. When the plague finally began to abate in 1350, one might have expected Christians to repent and mend their ways, especially since these were people who had never thought to question the existence of God and knew in their bones that his wrath came as punishment for sin. Instead, historians tell us the motto of the 1350s could have been “eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” People appear to have lived for the moment rather than returning to the arms of the church, turning toward anti-ecclesial religious movements or simple indifference. Some may have kept their distance because of some resentment against the church or clergy stemming from the plague years, others because they felt abandoned by God in their suffering.

Twenty-five years after the plague, the church would embarrass itself still further. Gregory XI tried to move the papacy back to Rome from Avignon and died in short order. Machiavellian political moves by French and Roman partisans led to there being two popes, one based in Rome, another in Avignon. For a brief time in the early fifteenth century there were actually three popes before the matter was finally resolved in 1417.

But the damage was done. People’s faith in the church — and perhaps, in some sense, in God —had been shaken. The Lollards, an English movement that drew inspiration from the teaching of John Wycliff, got started in these years, as did the Hussites, a Czech group that drew upon some of the same ideas. They felt that they could discern the Spirit’s leading apart from the institutional church, and sometimes that meant going directly against the church’s teaching — and, finally, even removing themselves from the church community.

What might the church have done or said to avoid adding the tragedy of discord and schism to the tragedy of the black death? What about individual priests and parishioners living in their local communities? Recall that historians know of no mass exodus of priests to the hinterlands to evade the sickness. Had priests been more zealous in being near to the dying and the bereaved during these months and years, they may have succeeded in comforting the brokenhearted, but they also might have succeeded in contracting the plague themselves and, particularly if it were the pneumonic variety, passing it on to others.

Obedience over heroism

Heroism alone, in other words, may have changed precious little. Massive numbers of men and women would still have died. Some others would still have shunned all discipline and church direction after the dead were buried. An inspiring local tale of a stout-hearted priest or a memorial for a beloved and admired local can rouse people to action, certainly, but those whose existence is forever marked by a human tragedy like the black death could be forgiven for wondering what that grand personage’s work actually changed.

No, heroism would not have dramatically changed outcomes for the church in the aftermath of the plague. The only thing that could have done that was obedience, an obedience which comes from faith. An obedient Clement might still have thought it best to quit Avignon, but he would have lived his life before that in solidarity with the poor. Individual Christians may still have found themselves confused by wild rumors, but they would have put their lives on the line to protect the Jews rather than being swept away in a torrent of accusations and fear of the other. Obedient priests, when possible, still may have kept their distance from plague victims, but they would have done whatever their calling required with confidence in God. Such a church would have faced the plague differently — and passed on their faith differently — because they were armed with the knowledge that love is stronger than death and that “as all die in Adam, so all will be made alive in Christ” (1 Cor. 15:22).

They would, in other words, have lived as if their days were in the hands of a God who raises the dead.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!