BANBRIDGE, Northern Ireland—I am seated on a train as I write this, slowly making my way north from Dublin to see family in Northern Ireland, the verdant Irish countryside rolling by on my left, the gray, glimmering Irish sea on my right, and acedia’s first whispers buffeting my mind like a tiny, malevolent gale.

I am not alone in this — not here in Ireland, where for a quarter-century Catholics have been rocked by one scandal, insult, and atrocity after another wrought by their church and its leadership — and not back home in the United States, where Catholic believers are wrestling with the substance and consequences of the latest nightmarish revelations about widespread abuses by their clergy and bishops.

There is a soulweariness shared by these ecclesiastical cousins on both sides of the Atlantic that pervades in the face of so much pain from the original insult, the resulting denials, obfuscation, and general mishandling; and, ultimately, the hope — that some measure of justice might be achieved and true healing commenced — repeatedly dashed.

Anger remains, yes, and rightly so, but it fast is being eclipsed by something more spiritually pernicious: ennui. “I just don’t care anymore,” and variations thereof are the sentiments I’ve heard expressed more than any other since Pope Francis arrived in Dublin last weekend.

In some quarters of this once thoroughly Catholic land, there was great expectation and optimism for what the papal visit — the first by a pope since John Paul II in 1979 — might do to renew and heal the wounded church. But that was not the prevailing mood, particularly among younger Irish, who have voted with their feet, marching away from the Church (and organized religion in general) in droves.

2018-08-25t170852z_1_lynxnpee7o0gf_rtroptp_4_pope-ireland.jpg

And yet, more than a few professional observers (myself included) believed there was an opportunity present to catalyze real change and even breathe new life into the Church if Pope Francis, whose warmth and natural pastoral instincts have made him beloved around the globe by Catholics, non-Catholics, and people who have no interested in religion at all, could turn it up to 11 and woo the disenchanted.

Alas, he tried.

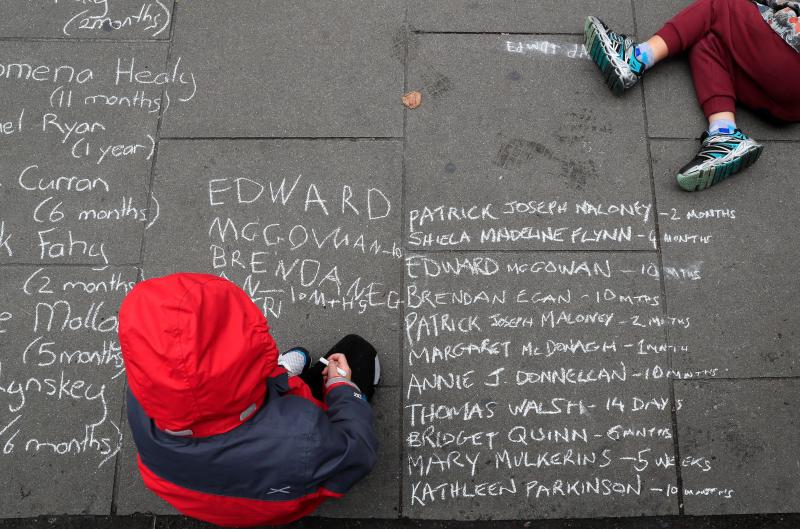

The Irish people wanted an apology for the abuse they’ve suffered — whether at the hands of pedophile priests and the complicit bishops who sheltered them and enabled their crimes to continue sometimes for decades, sadistic nuns at mother-and-baby homes or the Magdalene laundries, violent religious men and women who taught and oversaw various Catholic schools and institutions where precious children were treated with contempt, neglect, and too often vicious disregard.

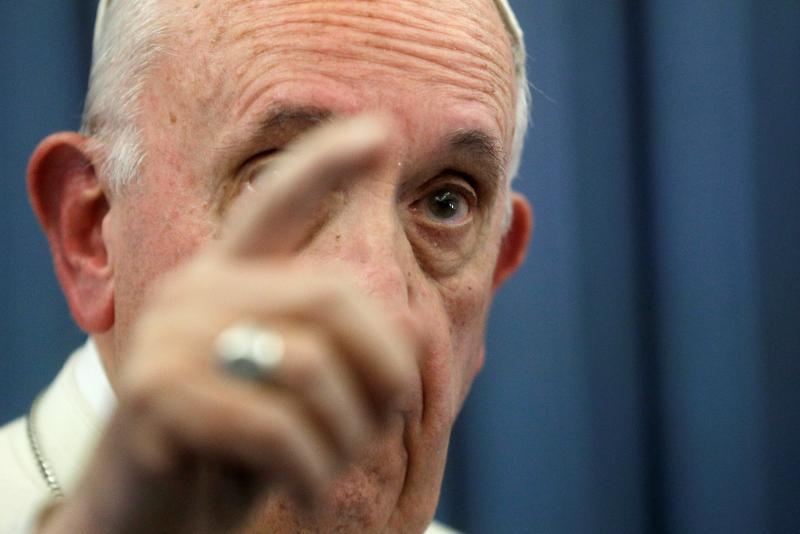

And he gave it to them. More or less, at least. On two occasions publicly and more that have been reported from private encounters during his Irish visit, Pope Francis asked for forgiveness. Speaking at the Marian shrine in Knock, County Mayo, he said, “I beg the Lord’s forgiveness for these sins and for the scandal and betrayal felt by so many others in God’s family.” He asked the Virgin Mary to intercede for the healing of survivors of abuse and to look with mercy on all the suffering member of her son’s family.”

At the papal Mass Sunday in Dublin’s Phoenix Park — the marquis event of his sojourn in Ireland, for which more than a half-million tickets had been distributed but only 130,000 ticketholders attended — the pope called an audible early in the Mass, adding an “off-the-cuff” litany of prayers for forgiveness for the abuses in Ireland, “abuses of power, conscience, and sexual abuses perpetrated by members with roles of responsibility in the church.”

img_7814.jpg

Pope Francis asked forgiveness — from God. What the Irish people didn’t hear was an apology directed to them. The pope didn’t say he was sorry to them. He didn’t ask them for forgiveness. It’s a subtle difference and sure, maybe they were meant to infer that he was apologizing to them and asking for their forgiveness as well as God’s.

Nevertheless, it was an omission that did not go unnoticed.

And then by the time Pope Francis was climbing up the steps of the Aer Lingus jetliner to fly back to Vatican City Aug. 26, just hours after his improvised mea culpa during the Mass, word of a fresh scandal from the United States was awaiting his response.

Accusations of cover-up

While the pope prepared for Mass in Dublin, a 7,000-word “testimony” penned by Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, the former papal-nuncio to the United States and a longtime adversary of Francis, was published. In it, Viganò claims the pontiff and several of his close advisers turned a blind-eye to the sexual misconduct of Theodore McCarrick, the emeritus cardinal-archbishop of Washington, D.C., who resigned in disgrace in late July after church officials received a credible accusation that he sexually abused a minor in 1971.

In his 11-page letter, Viganò, a staunch conservative with a clear grudge to bear against Pope Francis for ideological and personal reasons, levels numerous damning assertions against Pope Francis, the most damaging of which claims he knew of McCarrick’s alleged sexual misconduct (with adult seminarians and other priests), did nothing to stop it, and ignored restrictions Pope Benedict XVI (his immediate predecessor who resigned in 2013) had placed on McCarrick’s public ministry.

Asked about Viganò’s letter in a news conference aboard his flight home from Dublin to Rome, Francis advised journalists to "read the statement attentively and make your own judgment."

"I will not say a single word on this," the pope said of the letter, according to the National Catholic Reporter. "I think this statement speaks for itself, and you have the sufficient journalistic capacity to draw conclusions."

He continued: "When some time passes, and you have your conclusions, maybe I will speak. But I would like that your professional maturity carries out this task."

2018-08-27t011412z_3_lynxnpee7p0i9_rtroptp_4_pope-ireland.jpg

Hopefully a more thorough response is forthcoming from Pope Francis. Gone is the time when I’m-not-going-to-dignify-that-with-an-answer was an acceptable response from a spiritual leader or anyone else. If Viganò is, as many suspect, full of it, then the pope needs to say so. If there is truth to any of his allegations, the pope needs to say so, too.

This is no time to be worried about reputation or, frankly, dignity, unless it is the dignity of persons who have been abused. The fastest way to undo whatever goodwill might have been earned among Irish Catholics is to allow their friends and family and neighbors who have been abused in Ireland and elsewhere to be used as so many shuttlecocks — batted aloft or swatted to the ground on the adversarial side of some ecclesiastical net.

In the days since Pope Francis left Dublin, the Viganò scandal has eclipsed any news that was made (or not) in his 32 hours in Ireland, and how the pontiff and the Vatican will follow up on promises made publicly and privately to deal further with church abuse and its survivors here remains to be seen.

My impression from family, friends, people I interviewed and had conversations with, and what I overheard as a fly on the wall on trains and buses, standing in queues, and on more than one occasion in the sanctum sanctorum of a ladies room, is that many Irish people aren’t holding their breath — if they’re devoting any more time even to thinking about what the pope and his church might to do to make things right.

They’re tired. Too tired to give a damn any more. Too tired to fan the embers of hope that might remain in their hearts and minds.

'The loss of faith occurred off stage'

Before I caught the train north to County Down from Dublin, I stopped to see a new exhibit on the life and work of my favorite poet, Seamus Heaney, at the Bank of Ireland Culture & Heritage Center. Among the treasures featured in the multimedia exhibit “Listen Now Again,” is a version of the poem Heaney gifted me with in 2005 when I was writing my first book. I had asked the poet if he would grant an interview for the book — a collection of spiritual profiles of well-known people with whom I’d had one-on-one conversations about faith — but he very graciously demurred saying his spiritual life was something about which he was “woefully inarticulate.”

Instead, the great man gave me a poem to include in the book, and titled it, “A Found Poem.”* It reads:

Like everybody else, I bowed my head

during the consecration of the bread and wine,

lifted my eyes to the raised host and raised chalice,

believed (whatever it means) that a change occurred.I went to the altar rails and received the mystery

on my tongue, returned to my place, shut my eyes fast, made

an act of thanksgiving, opened my eyes and felt

time starting up again.There was never a scene

when I had it out with myself or with an other.

The loss of faith occurred off stage. Yet I cannot

disrespect words like “thanksgiving” or “host”

or even “communion wafer.” They have an undying

pallor and draw, like well water far down.

Heaney’s words, those of a man who left the church but for whom the vestiges of religion and faith remained somehow still meaningful, have come back to me often these last days in Ireland.

The loss of faith occurred off stage …

Yes, there are people who thought the papal visit to Ireland was wonderful, that it made great strides toward enlivening the faithful, that Pope Francis is warm and lovely, that they appreciated his asking forgiveness for the sins of abuse, that they believed more people would come back to the church because of it.

Maybe it will give way to a renewal in the church.

Maybe people will return to the pews and the family rosary and the collection plate.

Maybe they’ll have their children baptized as soon as they’re born the way it used to be for so many generations of our shared predecessors.

Maybe they’ll finally allow priests to marry, or women to enter the priesthood.

Maybe?

2018-08-27t011412z_2_lynxnpee7p0cr_rtroptp_4_pope-ireland.jpg

For many of us who have left one religious tradition for another, or who have abandoned organized religion or even faith altogether, there is a moment. A defining moment — large or small, public or private, dramatic or subtle — when the decision was made, when we’d had enough of the cruelty or the lies, the abuse or the incongruities, the hypocrisy or the apostasy, the nagging or the nastiness.

Whatever it is, and whenever it arrives, it is the proverbial bridge too far. And we walk away. Sometimes the person whose words or actions become the catalyst for our departure from the faith realize what they have done. Most of the time, they haven’t a clue.

I think of my Irish auntie, who arose before sunrise last Sunday to catch a bus from County Cavan to Phoenix Park in Dublin, so excited finally to get a chance to see a pope in person; who had to walk what felt like a few miles — in the rain — from the bus to the sprawling grounds where the papal Mass would be held, who held a ticket for a “corral” that was so far away from the altar and the route Pope Francis traveled in his pope mobile before the Mass began that she couldn’t get even a glimpse of him, and who had to “break the rules” and cross through several other “corrals” to reach a priest with the white-and-yellow umbrella who was serving the eucharist.

It was a long, cold, wet, undignified, sometimes frustrating day. But she was glad she was there, and she thought Pope Francis did a good job.

I thought of the volunteer ushers — scores of them from all over Ireland and beyond — who helped the crowd find its way and keep order throughout the lengthy Mass. “Some of them were very nice,” my auntie later told me, “but some of them were rough.” What if one of the rough ones had put up an arm and prevented her from taking communion because she wasn’t in the right “corral”? After more than 70 years of faith, could that have been the tipping point that tipped her out of the Church?

I think of one of her daughters, my cousin, who has been a lifelong person of faith. Several years ago, she went to Mass at her local parish, and an older man put up his arm and blocked her from approaching the altar during the Eucharist. At first, she thought it was a mistake, or that she had misunderstood, so she tried again, and again, up went his arm. Did he think she was someone else, someone who shouldn’t be allowed or had been excommunicated? She’s not divorced. She’s not a single mother. She’s a good Catholic woman, a prayer of rosaries, married in the church.

Why? She still doesn’t know. But she left and didn’t return for a long time.

And yet, she’s still Catholic. She still prays, still believes. She yearns for what Church can be: solace, community, direction, transcendence. They are, as Heaney says, “an undying pallor and draw, like well water far down.”

But, like so many others, the hurdle erected by one act of unkindness that becomes emblematic of a systemic problem in the body of Christ, takes effort to clear. And when you’re exhausted and there are too many hoops to jump through … maybe you stop jumping. Maybe you don’t bother any more.

Room for faith?

Before my train from Dublin pulled into the station in County Down, I opened my copy of Human Chain, Heaney’s 12th and final collection, and read a poem I somehow had missed previously. He called it “Miracle”** and it is inspired by the biblical story of a paralyzed man whose friends lowered him through the ceiling so he could see Jesus and be healed. It reads:

Not the one who takes up his bed and walks

But the ones who have known him all along

And cart him in —Their shoulders numb, the ache and stoop deeplocked

In their backs, the stretcher handles

Slippery with sweat. And no let-upUntil he’s strapped on tight, made tiltable

And raised to the tiled roof, then lowered for healing.

Be mindful of them as they stand and waitFor the burn of the paid-out ropes to cool,

Their slight lightheadedness and incredulity

To pass, those ones who had known him all along.

Aug. 30 marks is the fifth anniversary of Heaney’s death. I can’t help but wonder what he would have made of the papal visit and its aftermath, what words and images he might have conjured to put it in his inimitably clear-eyed perspective.

Perhaps there’s a clue in that last poem. What was the miracle that day in Capernum and was it singular? Heaney seems to suggest that another kind of miracle was present in the faithful friends of the man who had known him for so long, who once had walked with him when they were younger, and carried him when he no longer could. Men who knew him well in his fullness and complexity. He was no saint, surely. Neither were they.

Maybe they didn’t really buy into the whole “Jesus heals” thing. Maybe they were just humoring their sick friend and wanted to do something to encourage him. Maybe they were skeptical but not enough to rule out the existence of the supernatural and its power.

Whatever their motivation or belief, it was powerful enough to carry him to Capernum, climb upon the roof, tear off the tiles, hoist their friend up (carefully) to the hole, and, under the beating Judean sun, lower him to the floor below where Jesus could touch him.

That kind of faith — skeptical, stubborn, even unwitting — is miraculous.

What the future of the Catholic Church in Ireland might be is anyone’s guess. Institutional religion is on the decline and may never rise again to the heights my grandmother and forebears in this land experienced. But that doesn’t mean faith is dead.

The winds of acedia may blow in this fraught moment, but Ireland remains not only spiritually alive but vibrant, whether it appears that way from behind stained glass windows.

Look only to the laity — to the women and men, daughters and sons, fathers and mothers and aunties and cousins who are the heartbeat of the church even if they don’t darken its doors — for signs and wonders.

There, miracles may have sore muscles and wounded hearts, but faith abides.

Be mindful of them as they stand and wait

For the burn of the paid-out ropes to cool,

Their slight lightheadedness and incredulity

To pass, those ones who had known him all along.

++++++

*“A Found Poem” by Seamus Heaney appears in the author’s 2006 book, The God Factor , and later appeared, in slightly different form, as “Out of This World” in the Heaney’s 2006 collection District and Circle.

**By Seamus Heaney, from his 2011 collection, Human Chain

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!