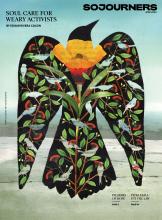

Illustration by Aldo Jarillo

Soul Care for Weary Activists

Many of us have made homes in religious traditions where we have found collective love, care, community-building, and resilience. But so much of what passes as spiritual in the United States — churches who only see their work as therapeutic, prosperity gospel proponents, white evangelical nationalists, New Age movements — is commodification by other means. John warns us against false prophets who, through quick fixes and distorted spiritual comforts, foster division and confusion in the service of lucrative self-aggrandizement.

I am an ordained minister in the Fellowship of Affirming Ministries, and I work as a movement chaplain in Los Angeles. I was trained as a spiritual director, and I have been doing ministry with faith-rooted activists since 2016. My work is informed by my primary training as a medical anthropologist and community researcher. I know that Jesus said that we humans are of more value than many sparrows, but I’ve found that we are a lot like them. We need refuge and sustenance. We need shelter. We need to nest somewhere. But with whom shall we do this for the short and long haul? And where shall we build our nests?

Read the Full Article

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!