Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

AFTER COLLEGE, I served as the musical arranger and pianist for a play based on the life of Amanda Berry Smith, a 19th-century Black woman evangelist who traveled the country and world preaching and singing. Born enslaved, she sang church hymns and spirituals. In the play, as in life, the spirituals contextualized Smith’s faith while subverting the power structures that undermined everything she was and was called to be. Fatigued by rejection from all sides but not hopeless, Smith, at the demand of a group of white clergymen, sang:

I got shoes, you got shoes

All of God’s children got shoes

When I get to heaven, gonna put on my shoes

I’m gonna dance all over God’s heaven

Heaven, heaven

Everybody talkin’ ’bout heaven ain’t going there

Gonna dance all over God’s heaven.

We rendered the spiritual lively and upbeat, as if Smith were putting it on for the clergymen, merriment in the face of subjection. The audience, however, was to understand the thinly veiled critique: Blending judgment and hope, the song affirmed that all God’s children have shoes, but in heaven, some of these children will put them on and dance. More pointedly, the song indicates that talking about God’s heaven isn’t the same as being a part of it. Over and against those who deny shoes while talking about heaven, the lyrics affirm God’s inclusivity, God’s resistance to scarcity, and God’s abundance. The spiritual posits that God’s heaven runs by a different calculus than this world and its dominant religious logic.

If I can say anything about heaven confidently, it’s this: Heaven cannot be an extension of the violence that denies God’s children their basic needs. Oppressive authority is utterly antithetical to God’s heaven; this is the message of the Bible and the songs of our ancestors. Yet as people like Smith knew, heaven is both freedom from an oppressive world and a heaven continuing that oppression.

The founder of Black liberation theology, James Cone, saw escapism as a problem in which too much “heaven-talk” leaves pressing political concerns unaddressed. Many theologians, activists, and Black preachers have followed suit. But escapism is the theological genius of the spiritual, even when it appears to refuse a political agenda. Heaven-talk refuses to allow a vision of God’s kingdom that runs on the logic of this world’s kingdoms. What Cone sees as the problem of escapism, I suggest is the very necessity of it.

DURING THE LATTER part of his career, Cone wrote in The Cross and the Lynching Tree:

… The Christian gospel is more than a transcendent reality, more than “going to heaven when I die, to shout salvation as I fly.” It is also an immanent reality—a powerful liberating presence among the poor right now in their midst, “building them up where they are torn down and propping them up on every leaning side.” The gospel is found wherever poor people struggle for justice, fighting for their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Bee Jenkins’s claims that “Jesus won’t fail you” was made in the heat of the struggle for civil rights in Mississippi, and such faith gave her strength and courage to fight for justice against overwhelming odds. Without concrete signs of divine presence in the lives of the poor, the gospel becomes simply an opiate; rather than liberating the powerless from humiliation and suffering, the gospel becomes a drug that helps them adjust to this world by looking for “pie in the sky.”

Progressive theological circles often animate this critique of heavenly mindedness to express a deep concern that an other-worldly focus fosters complacency. But to dismiss heaven-talk as “pie in the sky” is to misread the revelation of God in the imagination of the oppressed. It is our robust vision of heaven that first enables us to see how messed up this world is and then organize our lives not by a particular political vision, but beyond the limits of contemporary politics. Cone’s framing of the problem of heaven-talk and escapism leaves us with only one tool for fighting: direct political confrontation aimed at reforming the American experiment.

A robust theology of heaven does not dress up a dead corpse to make it look as if it is resting.

In his 1975 book, God of the Oppressed, Cone wrote, “the oppressed are called to fight against suffering by becoming God’s suffering servants in the world. This vocation is not a passive endurance of injustice but, rather, a political and social praxis of liberation in the world, relieving the suffering of the little ones and proclaiming that God has freed them to struggle for the fulfillment of humanity.” Cone is concerned with the “practical elimination” of suffering and not with its theoretical constructions. To Cone, heaven-talk is a distraction from more practical efforts.

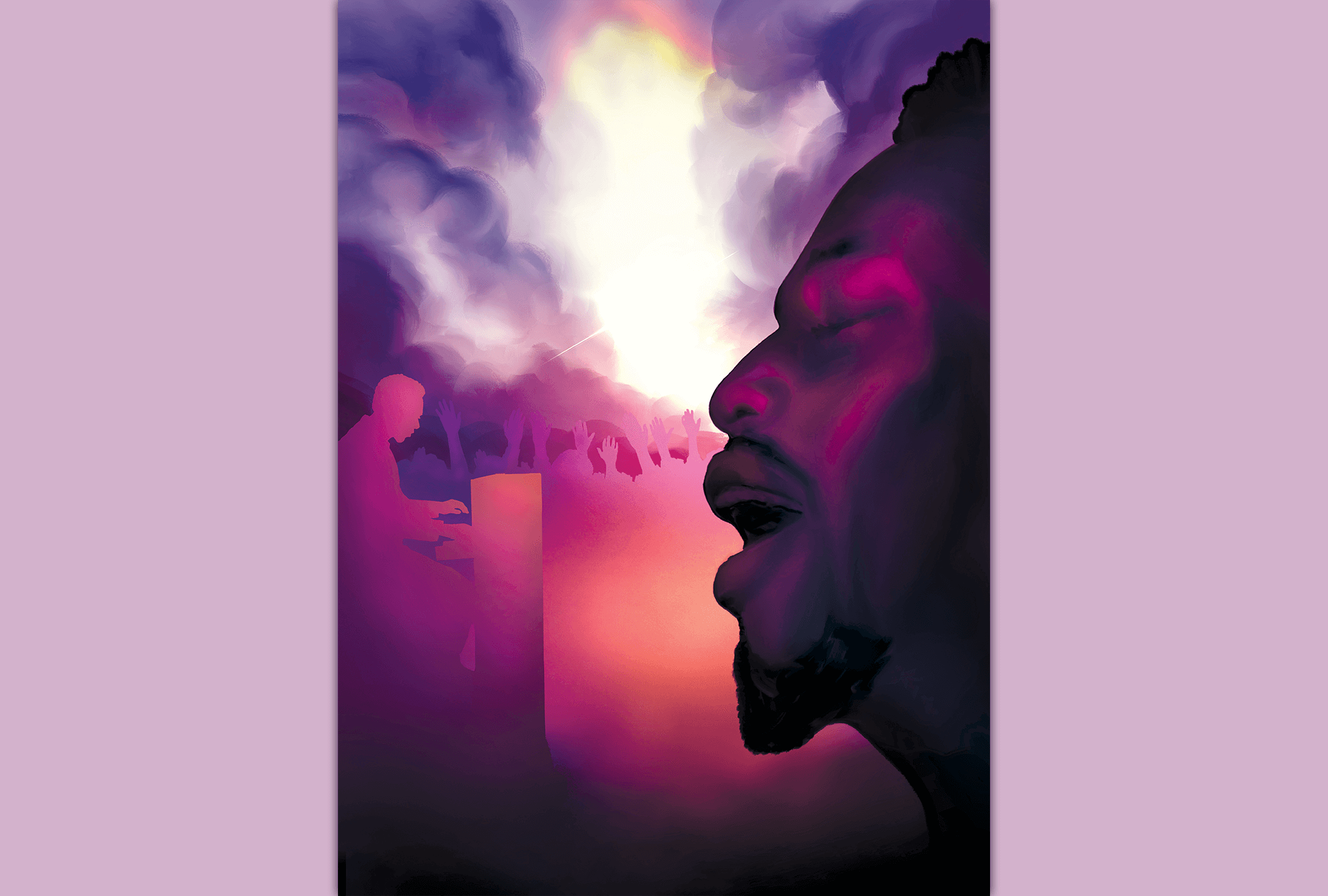

Illustrations by Matt Williams

I REFUSE TO dismiss or discipline escapism. Instead, I believe escapism is the political theology that allows us to see this world’s political game for what it is: hellish, death-dealing, and anti-God. Heaven-talk is the good news that pulls the thin façade of hope off the political schemes of this world, and that’s radical. A robust theology of heaven does not dress up a dead corpse to make it look as if it is resting. It stops looking for the living among the dead and beholds, even if cautiously, the potent power of resurrection.

The spirituals invite us to register the troubles of this world as something other than incidental, but constitutive of this age: They are everywhere and they are not God. The grace of the spirituals’ revelatory power rests in how they enable the oppressed to engage a God who is not of this world but whose revelation in this world does not require us to fight fire with fire or trust in the weapons of America’s warfare.

The revelatory nature of the spirituals goes beyond coded text for escaping the plantation physically. As theological forms of redress, the spirituals dare to imagine a form of existence where the laws and violence of the plantation are no more. That means the spirituals embody a spiritual interiority that the plantation and the world it creates cannot conceive. They remind us, as a regular practice, that we do not have to settle for this old world.

Heaven’s freedom has to overcome oppression not as mere play in a zero-sum game, but as the total refusal of the game itself.

CONE CONTINUED IN God of the Oppressed that “in the experience of the cross and resurrection, we know not only that black suffering is wrong but that it has been overcome in Jesus Christ. This faith in Jesus’ victory over suffering is a once-for-all event of liberation. No matter what happens to us in this world, God has already given us a perspective on humanity that cannot be taken away with guns and bullets.” I could not agree more with Cone here, but to guns and bullets I would add gerrymandering and ballot boxes. The refusal to let this world’s violence have the final say is a witness born in the possibility of credible escape. Part of our fighting is a categorical refusal of the world’s meanings and definitions, not just fighting to be accepted and included in the world’s project. Why use our best energies to enter a house divided against itself, a house built on sinking sand? Freedom and liberation cannot only mean having proper citizenship and standing in a country that is not built for eternity.

Cone’s commitment to a “fight” must ultimately bear witness to God’s revelation of freedom in Christ, not the world. A great America is not the end goal of our salvation. Cone, in critiquing escapism, misses the many ways victory can emerge and produce otherworldly possibilities even now. In a simple way, these victories are akin to the miracles marking Jesus’ ministry. For us, they show up in the everyday practices of care, belonging, and mutuality that disrupt the abject status that anti-Blackness seeds. Cone’s masculinist vision of liberation and freedom conflates dignity and selfhood with a narrow representation of resistance; he misses the inherent power in feeding the kids on the block, intricately caring for each other’s hair, and sharing limited resources to ensure everyone has something. These are not grand gestures, but they are gestures that disrupt the status quo of dehumanization.

Liberation as imagined in this world’s political process is not synonymous with God’s heaven. Liberation here ultimately fails as the false hope of the nation-state. When we conflate the gospel of this country’s founding documents and principles with the good news of Jesus Christ, we do a disservice to our spiritual imagination and our faith. The country’s ideals and vision of a good life pale in comparison to what God has in store. Heaven is not a reformed world; it is the end of the world’s oppressive organizing principle.

Illustrations by Matt Williams

THEOLOGICAL REVERSALS (such as in Matthew’s gospel—“the first shall be last and the last shall be first” 20:16, or “such as you’ve done to the least of these, you’ve done to me” in 25:35-40), achieve a heavenly end by different means. Returning to the spiritual lifted by Smith, the subtle invitation is not a fight to have shoes, but a matter of putting them on and dancing before God, even as those who would see you without shoes are not even in the space you and God inhabit. This too is escapism, but it shows up as a reversal of exclusion.

This is where Cone’s discernment of God’s fidelity to the oppressed is most salient. Small acts of holy witness—like dancing in shoes one already has, or barefoot by choice—can function as profound resistance without necessarily conforming to the world’s understanding of struggle.

These small acts operate as holy witness precisely because they refuse to engage power on its own terms. They embody a different sovereignty, a different logic of resistance that does not rely on direct confrontation but rather on the creation of alternative spaces and practices that bear witness to heaven’s reality breaking into earth. Heaven’s freedom must overcome oppression not as mere play in a zero-sum game, but as the total refusal of the game itself.

THE GIFT OF spiritual revelation uproots the world’s political staging as the be-all and end-all of how we relate with each other. Where we must push further is in imagining a God whose sovereignty does not function according to the laws of the world and the state. God is not king in the way the empire stages the king. God is not love how the empire stages love. The revelation is not just an invitation to a resistance that competes in the state’s arena; it is a revelation that undermines the very legitimacy of the world’s violence.

The difference between heaven and earth, as given to us in the Lord’s Prayer, concerns earth’s need to enact God’s will as it is enacted in heaven. This assumes that the will operative on the earth is not the will operative in heaven. It should then stand to reason that when God’s will is operative on the earth as it is in heaven, all will have the bread they need—conditions that are fruitful for living. The prayer does not render this an issue of scarcity or abundance, but it frames the capacity to sustain in God’s agency. The powers that undermine bread for all, that make living impossible, are forces that are at odds with God’s heaven and God’s generosity.

Why use our best energies to enter a house divided against itself, a house built on sinking sand?

IN THE PRESENT moment, it feels like we are witnessing unprecedented political turmoil and upheaval. Alas, this is the way of the world. But, in the face of such violence, we tarry for visions of heaven’s otherworldliness to embolden our divestment from all the false versions of heaven and a good life this world promises that still use violence as the assurance of liberty.

Without God’s vision of heaven, we do not know what God’s will concerning humans is. Whatever it means to be human cannot be defined by the practices of citizenship germane to the human rights discourse of modern nation-states. And for as much as it matters that our bodies escape violence, it seems just as urgent for our minds to escape a totalizing political project that in every way only wants to reify its false legitimacy. Only God is sovereign, and no amount of political idealism can quench the soul’s thirst designed by God to be for God.

When Joe Hill, a Swedish-American labor activist, penned the song “The Preacher and the Slave” in the early 1900s, he had no experience of enslavement but used the enslaved person as a foil for the gullible one who chooses faith over real material needs. Hill’s rousing chorus ended with the phrase, “You’ll get pie in the sky when you die (that’s a lie).” When Cone levies that line against the descendants of those who Hill used to make a point about white laborers’ rights, he misses an opportunity to escape the very logic his liberation theology aims to undermine.

We cannot afford to surrender the “beams of heaven” (words penned by a contemporary of Hill’s, the Black Methodist preacher Rev. Charles A. Tindley) to the apparatus that intends to extend desolation in all directions. We must hold to a vision that affirms over and again that heaven certainly ain’t this mess, ensuring we keep sight of the best over against the worst.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!