Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

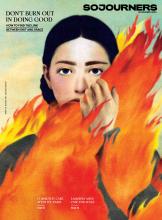

LYNN, A WHITE woman in her 40s, sank into a porch chair beside me. I’d come to interview her neighbor, but when Lynn heard I was conducting research on the ways white Christians develop long-term commitments to racial justice, she asked to talk.

Lynn said she grew up in a Christian family in a white neighborhood where people didn’t talk about race. At a Christian college, professors taught about social injustices in a way she’d never encountered, inspiring her to join a summerlong internship designed to train young Christians to pursue justice. As she met people who had been doing this work longer than her lifetime, she began to wonder how they persevered. “I was working with people who had been in it for the long haul, and I’d ask them, ‘How do you keep it up? How have you been doing this so long? You burned your draft card in, like, 1969? And you’re still going? And you still somehow believe that the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice? Like, how?’” She worried she didn’t have the tenacity they had.

Her story sounded like the buildup to a punchy life lesson, so when she paused for a drink of water I asked, “What would you tell your former self now?”

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!