Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

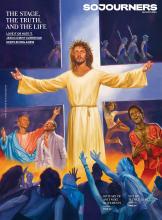

MORE THAN FIVE decades ago, two young Brits with dreams of writing musicals came up with the audacious idea of a rock opera about the Passion of Jesus Christ, told from the point of view of Jesus’ betrayer, Judas Iscariot. From the very moment composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and songwriter Tim Rice proposed it, Jesus Christ Superstar provoked both adulation and condemnation. And five decades have done nothing to diminish either the show’s fire or the intensity of audience reactions.

In August, the Hollywood Bowl will host the musical with another innovative twist: Wicked’s Cynthia Erivo plays Jesus and rock star Adam Lambert takes on Judas, in a one-weekend-only production directed by Tony and Emmy Award winner Sergio Trujillo. Some have already condemned the production for giving a queer Black woman the role of Jesus, decrying it as “intentionally blasphemous” — a complaint that has been made about various aspects of the show (including its casting) from the beginning. But the show’s actual history reveals that Superstar has been anything but a blight upon Christianity. Generations of artists have found within it fertile ground to reflect on faith and justice, sacrifice and society.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!