Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

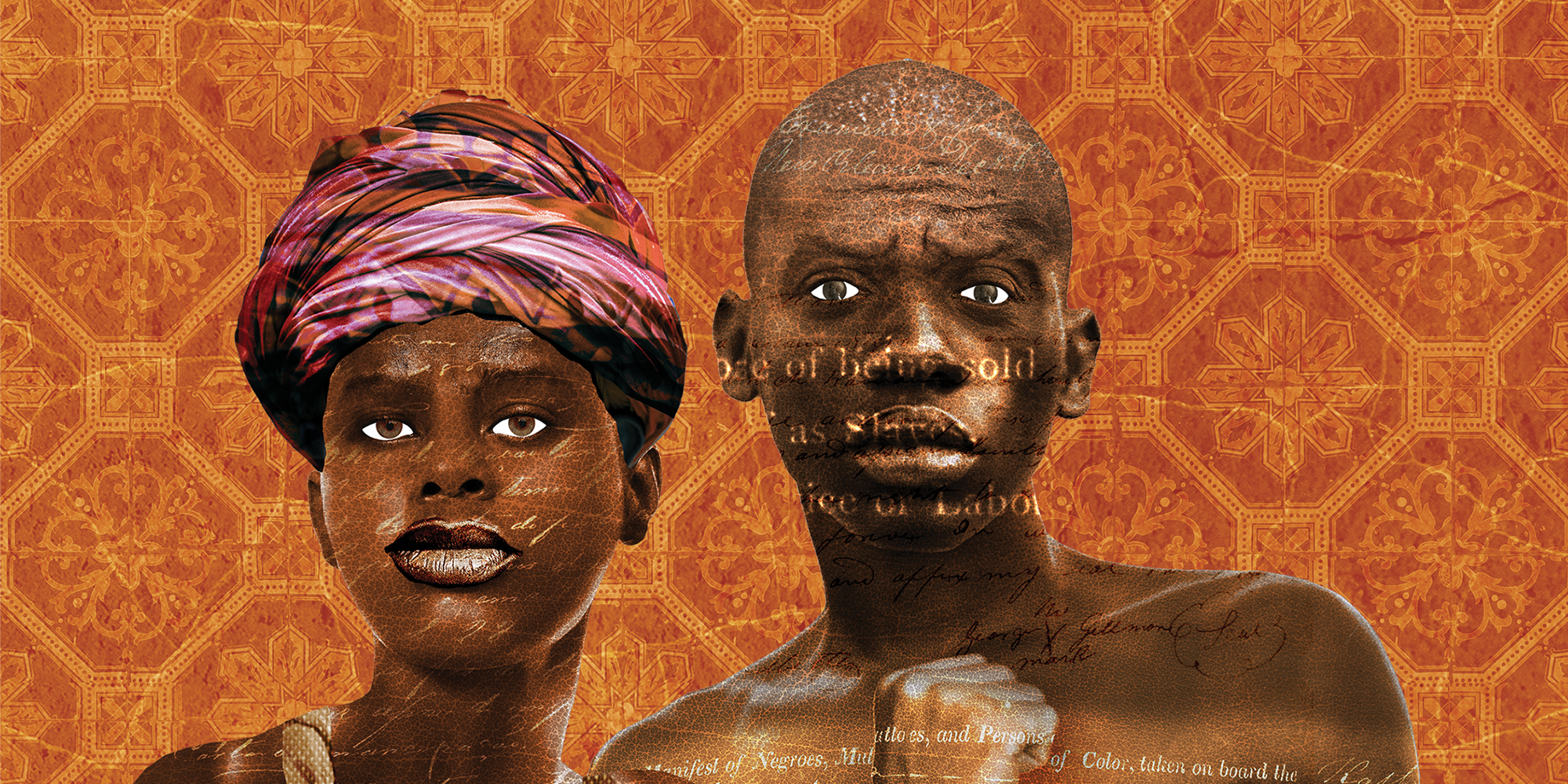

Illustration by Dave McClinton

TO THE BEST of our historical knowledge, in August 1619 a ship named White Lion landed at a coastal port near Point Comfort, Va., carrying 20 to 30 captive Africans to be sold into slavery. This landing symbolizes the construction of race as a defining and indelible feature of America’s core identity. It stamped black bodies with the ineradicable identity of subhuman chattel. As such, it signaled the white supremacist foundation upon which America’s capitalistic democracy, with all its sociopolitical systems and structures, would be built.

Today, the legacy of the White Lion landing prevails in almost every sector of American life. Black people continue to suffer 21st century versions of slavery, such as poverty, mass incarceration, and substandard schools. More than 400 years after the White Lion landing, two things are clear: As Nikole Hannah-Jones reminds us in The New York Times’ 1619 Project, there has never “been a genuine effort to redress the wrongs of slavery and the century of racial apartheid that followed,” and there has been no genuine effort to truly end white supremacist injustice itself. Consequently, there have been renewed calls for reparations.

THE IDEA OF reparations was brought back to public attention in 2014 when Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote “The Case for Reparations” in The Atlantic, making clear that until the nation reckons with its “compounding moral debts, America will never be whole.” As this is true for the nation in general, it is likewise true for faith communities, as the authors of what became known as the Black Manifesto recognized more than 50 years ago.

In May 1969, civil rights leader James Forman disrupted the services of Riverside Church in Manhattan to deliver the Black Manifesto written at the National Black Economic Development Conference, which had convened in Detroit. The manifesto demanded $500 million for reparations from “white churches and Jewish synagogues” for “aiding and abetting” the “exploitation of colored peoples around the world.”

This money was to be used for a range of programs to support economic growth, educational opportunities, and the psychological well-being of the black community.

While some white and Jewish faith communities, as well as seminaries, responded by giving funds to various projects and organizations within the black community, the Black Manifesto’s goals never came to fruition.

Now, more than 50 years later, various religious institutions and faith communities are responding to the renewed call for reparations by Coates and others. For example, the Episcopal Church’s Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria has set aside $1.7 million for a reparations fund. Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey established a $27 million endowed fund to address historical theft of labor and discrimination. These and other institutions have set up funds to pay or provide scholarships to descendants of the enslaved people who provided the labor upon which their buildings and wealth have been built, while also finding ways to support various black ministries. However, the question remains: Is this enough?

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!