Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

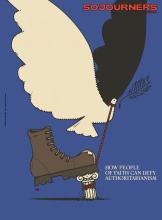

Illustrations by Sam Lubicz

“ONE OF THE TRADITIONS of St. Patrick is an old prayer that he wrote called ‘St. Patrick’s Breastplate,’” explained Father David Rose of St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Rincon, Ga., to the half-dozen men who’d gathered around him. “It’s more like an epic poem, like an old epic Celtic poem, but it’s a prayer.”

“I bind unto myself today / the strong Name of the Trinity,” he continued, reciting stanzas of the 1,500-year-old prayer. “By invocation of the same / The Three in One and One in Three / Of Whom all nature hath creation / Eternal Father, Spirit, Word: Praise to the Lord of my salvation / Salvation is of Christ the Lord!”

Father Rose wasn’t addressing his fellows from the pulpit, however, nor were they gathered in the basement or rectory of St. Luke’s. Instead, he was speaking to a group of Dungeons & Dragons players at Savannah Lion Games in Pooler, Ga., at a table covered in rulebooks and dice rather than Bibles and hymnals.

Welcome to Game Church.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!