Film

When Jon Stewart took a hiatus from The Daily Show a little over a year ago to film Rosewater, I’ll admit, I, along with other loyal viewers, was intrigued but skeptical. I was already aware of the story of Maziar Bahari, an Iranian-born journalist for Newsweek who’d been imprisoned and tortured by Iranian officials for nearly four months, detained in part because he’d sat for an interview with The Daily Show’s Jason Jones. But the rumors circulating that the film (based on Bahari’s memoir) would be partly comedic seemed … risky. Far be it from me to question Stewart’s satirical prowess, but films about political prisoners rarely leave room for laughter.

But of course, nobody needed to worry. Stewart’s penchant for pointing out the absurd is what makes Rosewater unique among films of its kind. Where movies like Hunger focus on the brutality of imprisonment (and rightly so), Rosewater’s goal is different. It sets out to explore the personality of people like Bahari’s jailers, the Kafkaesque nature of life in Iran under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and the creativity it takes to survive in such a setting.

In the film, Bahari (Gael Garcia Bernal) leaves London, and his pregnant wife, to cover Iran’s controversial 2009 presidential election. He meets and interviews Iranians working for Ahmadinejad’s campaign, as well as those subverting the system and working for change — one scene has Bahari led up to an apartment roof covered with contraband satellite dishes. When there are accusations of fraud after the elections, followed by widespread protests, Bahari is arrested as a foreign spy. He’s held in solitary confinement, and interrogated and tortured by a man known only as Rosewater (so named for the smell of his perfume).

While there are scenes of physical torture onscreen, the film doesn’t show them in graphic detail — to the point where it almost feels that Stewart isn’t going as deep with the subject matter as he could have. But it does something instead that feels far more important.

The new Stephen Hawking biopic The Theory of Everything, presents the relationship between the famed physicist and his first wife, Jane, in beautiful display. Screenwriter Anthony McCarten described the underlying theme of the film such:

“If all of us were some kind of cosmic accident, what chance love? That’s the point at which science breaks down, and something else exists.”

That rift between the proofs and facts that drive Hawking (played by Eddie Redmayne) and the “something else” represented by the inspiring story at its center is one that reflects a larger conversation about faith, science, and the unknown that feels like it’s been a part of culture from the beginning of time (all puns aside). It’s unfortunate, then, that the film doesn’t take the opportunity to explore those discussions beyond the surface level.

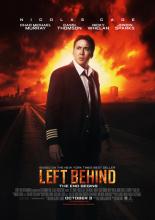

LEFT BEHIND may be a soft target, but once seen, you may realize that it’s a soft target for anyone who has ever been on an airplane, seen what Nicolas Cage is capable of in Leaving Las Vegas, met a Muslim, or not been cryogenically frozen since the era when it was socially acceptable to treat people with dwarfism as punchlines.

It really is worse than most theatrically released movies—shot and edited like a political attack ad/music video mashup, written like a child’s Sunday school lesson, and then strangely denuded of almost anything that would make it identifiably Christian (teasing those who already believe, yet scared of alienating people who just want to see a cheesy disaster movie without heavy proselytization).

The people who made it aren’t bad people, of course. (I’m not sure anyone is, with the line between good and evil running through each human heart and all—although that’s another argument that wouldn’t make it into this film.) The producers are ideologically committed to advancing a message that they were indoctrinated into by an unthinking system—let’s call it the Christian Industrial Entertainment Complex. They’ve stumbled upon the money and basic skill to make movies. They think that what they’re doing is changing the world for the better, but that’s doubtful—it’s more likely just reinforcing the closed-set worldview of the CIEC’s pre-committed adherents. This isn’t new, so I’m not too concerned about one more example of bad art masquerading as religious experience.

It might be tempting for some viewers to see Dear White People as over-the-top. To see some of its characters as caricatures, or the offensive party that makes up its climax — with white students dressed in blackface — as unrealistic. But it’s not. For evidence, you only need to look as far as the credits, which show photos from similar events at other schools across the country. And when the president of Winchester claims that “racism is over in America,” it doesn’t sound too different from Bill O’Reilly’s similar claim on The Daily Show just last week.

Dear White People is clever, loving, angry satire. It’s a multi-faceted exploration of race in a time when such portrayals are needed, like peroxide on a deep cut. The film sometimes falters in its process, but delivers the goods when it matters most. The fact that it comes so stingingly close to reality is stunning. It’s funny. It’s sad.

CHEF IS A small-budget film with an all-star cast and artful storytelling. Jon Favreau, who also directed Iron Man, stars in his own film as a head chef named Carl Casper at an acclaimed restaurant in Los Angeles. Casper is left in a vocational tailspin after a scathing review and a public meltdown. He loses his inspiration and finds himself in an existential crisis.

In Chef Casper’s quest to recover his culinary mojo, he takes a trip to Miami and buys a used food truck. The film plays on the power of relationships in a messy, winding, but authentic path. Chef Casper’s community—his ex-wife, his son, and his best friend—are invited into the one thing Casper loves to do, demonstrating how community, at its best, can propel us on the way we should go.

Each truck stop on the journey back to California fills Chef Casper with new vision and adds distinctive ingredients. He makes his way to once again bring beauty and flourishing back to his street corner of the world.

My small group at church watched Chef together and bonded over it. We explored themes of vocation—how we can contribute to flourishing through the distinctive things “we’re good at.” And how activism isn’t just about waving the proverbial picket sign; it also can be about loving what we do with great friends.

HIGHBROW FILM criticism and fanboy comment pages alike often manifest as if their purpose is to make snarky points about who knows how much about what. Whether in an academic journal or on Reddit, film criticism can either get the point or be the point. We can either convince ourselves that we exist to show the world how smart we (think we) are—or to facilitate a conversation about the purpose of art that’s spacious enough to stimulate both the heart and the mind.

The lack of clarity about such purpose means that it has to be continually reasserted, so here goes: The purpose of art is to help us live better. I contend that this is the primary evaluative lens through which we should watch. Of course aesthetics, craft, and content matter, but how I watch films depends at least as much on the notion that art emerges from a human creative impulse that is at its best directed at the common good.

The protagonist of the new documentary The Overnighters has made a similar shift in consciousness regarding his own vocation. North Dakota pastor Jay Reinke understands that the purpose of church isn’t far different from that of art, and he opens his building to economically disenfranchised folk trying to find a job in the oil boom, letting them stay overnight despite local suspicions. It’s a manifestation of Christian vocation mingled with lightly ringing alarm bells—the pastor appears to be a Lone Ranger, not collaborating with supportive church leaders or members; the jobs are in an environmentally degrading industry—and a picture of community service that seems at once miraculous and exhausting.

Two new movies that aim to attract a faith-based crowd join a glut of biblical films for 2014, testing the limits of Hollywood’s appetite for religion.

The two films, “The Good Lie” and “Left Behind,” both opening Oct. 3, reflect two different filmmaking strategies: One is geared for a wider audience that could attract Christians, while the other produces a movie clearly made for the Christian base.

With a number of films targeting a faith audience this year, it’s unclear whether Hollywood is oversaturating the market with faith-based films — a revolutionary idea 10 years after Mel Gibson’s “The Passion of the Christ” shocked the industry by raking in $611.9 million worldwide.

“The Good Lie,” starring Reese Witherspoon helping four young “Lost Boys” from Sudan adjust to life in the U.S., has underlying faith themes. The refugees rely on their faith as they try to leave homeland strife behind, and Witherspoon’s character works closely with a faith-based agency to place refugees with families.

These days, female television characters can almost do it all. But we, the media consumers and producers, are still deciding if we should let them make mistakes, too.

And I don’t mean just the I-dated-the-wrong-handsome-doctor mistakes, or the I’m-an-overprotective-mother mistakes. I mean the type of mistakes that warrant the label of antihero. Merriam-Webster defines an antihero as “a protagonist or notable figure who is conspicuously lacking in heroic qualities.” Over the past several years, TV has become saturated with male antiheroes. Breaking Bad made a meth dealer Emmy gold, and Dexter garnered a cult following behind a sociopathic vigilante. But hey, boys will be boys.

Girls will be girls, too, if we let them. And girls aren’t always perfect. John Landgraf, president of FX, says it’s much harder to find acceptance for the female antihero: “It's fascinating to me that we just have really different, and I think, a more rigorous set of standards for female characters than we do for male characters in this society.”

Editor’s Note: ‘Left Behind’ starring Nicolas Cage hits theaters nationwide on Friday, Oct. 3. The film is based on the wildly popular book series and movies of the same title, in which God raptures believers and leaves unbelievers behind to learn follow Jesus and defeat the Antichrist. So how’s the film reboot?

Sojourners Web editors called up a group of religion writers in D.C. to watch and review the movie together. We left with more questions than answers. Here’s our takeaway on all things ‘Left Behind’ — and a little Nic Cage.

Catherine Woodiwiss, Associate Web Editor, Sojourners: So first things first — why Left Behind again?

When the books were published [starting in 1995], there was a debate happening in Christianity over whether Hell was a real, physical place. And the original movies were produced in the context of 9/11 and the Iraq war. So you can look and say, okay, this was a time of questioning what some saw as fundamental beliefs, of war and terrorism. So the popularity of an end-times series makes some sense.

But why now? Why today?

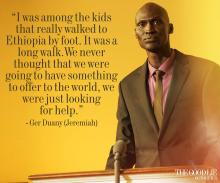

As the Washington, D.C., premiere of Warner Bros.’ new movie, The Good Lie, came to a close, I could barely see the credits through my tears, but the noise of the crowd around me erupting into cheers and the standing ovation was impossible to miss. This film really touched me. I knew I had to write about it.

The Good Lie is the story of some of the "Lost Boys" of Sudan — orphans of war, who walked hundreds of miles fleeing violence, only to spend a decade in a refugee camp before finally being resettled in America. But the film is much more than that. It is a story about the power of faith and regular people who do incredible things because there is no one else who can. It is the story of immigrants — a funny and heartbreaking insight into what it is like to be a stranger in America. And it's a story and performance made all the more real because the Sudanese characters are played by actors who were child refugees and child soldiers themselves.

It stars Reese Witherspoon, whose character and role encapsulate so much of why this movie works. She's the headline draw for Warner Bros., but the movie is not about her. She helps the Lost Boys, but as is so often the case when we respond to God's call to care for our neighbor, they probably help her more. No one saves the day in this movie, but they all help save each other.

“God has to be busy with everyone else. And hopefully he will come into my life. I hope it happens. It’s going to break my heart if it don’t.”

So says Andrew, one of the three teenage subjects of the documentary Rich Hill, currently playing in theaters across the country. While film refrains from any sermonizing on poverty, or any direct call to action from its audience, it’s mighty hard for socially minded Christians to hear these words and not feel compelled to react. Tracy Droz Tragos and Andrew Droz Palermo’s documentary is an unflinching portrait of poverty in rural America, and its sympathetic portrayals give heartbreaking examples of neighbors in need.

The film follows a year in the lives of three boys: Andrew, Harley, and Appachey. They don’t know each other, but they have much in common. Besides living in the small town of Rich Hill, Mo., all three come from troubled families living well below the poverty line. Andrew is the most hopeful of the group. He’s got a family he loves, and a father who means well, but whose unrealistic dreams keep the family moving from place to place and dodging unpaid bills. Thirteen-year-old Appachey and 15-year-old Harley, however, come from darker situations. Harley is a victim of sexual abuse (his mother is in jail for attempting to kill the man responsible), while Appachey’s violent behavioral issues are simply too much to handle for his single mom, overwhelmed with his siblings and a dilapidated house filled to the rafters with junk.

Editor's Note: Spoilers ahead! You've been warned.

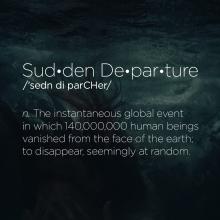

Over the past eight episodes of The Leftovers, HBO’s latest drama based on Tom Perrotta’s play of the same name, viewers have been treated to a case study in grief and faith in the midst of a life-changing event. Unlike the Left Behind series, which incorporated Christian triumphalism with terrible theology, The Leftovers examines the deeper human and spiritual issues of what would happen were two percent of the population to suddenly disappear. It is powerful and beautiful and really hard to watch (especially Episode Five). It asks the question: does life go on when your world is changed forever?

The show offers a variety of responses to the Sudden Departure of October 14: Kevin Garvey, the police chief who seems to be losing his mind after his wife leaves him for a cult and after his father needs to be committed; Nora Durst, who’s lost her entire family, so she keeps everything exactly as it was when the Sudden Departure occurred; Rev. Matt Jamison, Nora’s brother whose faith has been shaken because he was not taken; the town dogs who have become feral; and finally, the creepiest citizens of Mapleton, the Guilty Remnant, or the GR as they’re “affectionately” known.

This past week’s episode gave us a greater understanding of the GR. Although the nihilistic views of the Guilty Remnant are quite different from those of Christianity, I was struck by their powerful and strategic mission of witness. The cult was formed out of the recognition that everything changed on October 14 and that to pretend otherwise was foolish. The group, in their white clothes, their silence, their stripped-down existence, bears witness to the fact that they are living reminders of what happened. They are fundamentalists about their cause and willing to die for it — even if that death comes from their own hands.

We lost a funny man on Monday to a sad and persistent disease. Robin Williams passed away last night of an apparent suicide.

In memory of Williams, we've compiled a few of our favorite scenes.

1. Aladdin

Williams' performance as the lovable Genie: "Ten thousand years will give you such a crick in the neck!"

This Friday, a movie version of the classic novel “The Giver” opens in theaters with an impressive cast, including Oscar winners Meryl Streep and Jeff Bridges. “The Giver,” originally written by Lois Lowry, explores a seemingly perfect world where all conflicts have been resolved and annoyances — such as bad weather and adolescent “stirrings” — have been eradicated, allowing this culture to achieve a beautiful state of “sameness.”

As you can imagine, this utopian society is not so utopian. “The Giver” focuses on young Jonas, who has been selected for a daunting task: to serve as society’s sole proprietor of memory and emotion. Jonas learns about pain and sadness, but also experiences beautiful colors, a thrilling sleigh ride and ultimately learns to feel love. In other words, Jonas learns what it means to be human — and that his world may not be so perfect after all.

“The Giver” is the latest in a wave of dystopian stories that have washed over America in recent years. From this summer’s “Purge” sequel and “Under the Dome” to the latest “Hunger Games” movie (due out in November), people can’t get enough of these apocalyptic fantasies, in which seemingly perfect worlds turn horrific.

Why such an appetite for dystopian stories now?

WHAT’S A GOOD priest for? So asks Calvary, the second feature film from writer-director John Michael McDonagh, rooting itself in Ireland’s coastal landscape, centering on a pastor threatened with scapegoat-retributive murder from a grievously sinned-against parishioner. Its vibe owes a great deal to the quiet reflection of films such as Jesus of Montreal and Au Hasard Balthazar (in which a donkey evokes the love and wounds of Christ), and the archetypal Westerns High Noon and Unforgiven. Brendan Gleeson plays a priest who was drawn into the church after his wife’s death, which allows us the rare experience of seeing a cinematic Catholic priest who is both a parent to his flock and to a beloved daughter, who feels somewhat abandoned by his commitment to the church.

Gleeson has the uncanny ability to hold his massive frame as both solid—almost concrete—and vulnerable. Knowing that everyone is both broken and breaker, his Father James is healing on behalf of a flawed institution, although he doesn’t confuse vocation with a job. His bishop’s response to a request for help is “I’m not saying anything,” reminding me of Daniel Berrigan’s challenge to religious hierarchies, heard at a public meeting in Dublin in the run-up to the Iraq war: “In Vietnam, they had nothing to say, and said nothing; now, they have nothing to say, and they’re saying it.”

Father James understands the difference between stewarding power and grabbing it (one obvious signal of his goodness), and he is up to his neck in the community, running the gamut from friendship with an American writer looking for inspiration in the land of his presumed ancestors to a visit with a former pupil whose own inner darkness has led him to do monstrous things.

IT’S A TRUISM to say that television is outpacing cinema for entertainment quality and depth of exploration. Since The Wire appeared a decade ago, studios have been realizing that there is an audience for long-form storytelling that is willing to think.

Recently I’ve been struck by the set-in-the-’80s espionage thriller The Americans, the deeply haunting police procedural True Detective, the hilarious pathos of Louie and Veep, and the sly, shocking Hannibal, a prequel to The Silence of the Lambs: All hugely entertaining, dramatically credible, and challenging both as works that require sustained attention and in terms of what they say about life. The Americans is really an exploration of marriage and cultural identity wrapped up in Cold War cloaks-and-daggers; True Detective is a lament for the broken parts of America, and an affirmation that friendship endures above almost everything else; and Hannibal is a postmodern delving into Dante’s Inferno, looking at the underbelly of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s assertion that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

What’s most exciting is that it’s now considered viable to make drama that actually asks real questions about life and is prepared not to answer them pat. Along with the vast amount of social media conversation about these works, what we have is more akin to ancient forms of public entertainment that required a kind of audience participation—theatrical catharsis meeting gathered conversation to produce a community hermeneutic. When we talk about TV and cinema, we’re talking about ourselves.

HBO’s “The Leftovers” is the feel-good series of the summer, if your summer revolves around root canals and recreational waterboarding.

Indeed, it’s pretty grim stuff — but quite engrossing and worth your time, thanks to intense performances by Justin Theroux and Christopher Eccleston, and the way creators Tom Perrotta, who wrote the book on which the series is based, and Damon Lindelof, best known for screwing up the end of “Lost,” unflinchingly tackle the nature of grief and the limits of faith.

Can you call it an apocalypse if you can still get a decent bagel afterwards? It’s three years after what has been termed the Sudden Departure, when 2 percent of the world’s population — Christians, Jews, Muslims, straight, gay, white, black, brown, and Gary Busey — suddenly disappeared.

"Here's how you bring light into the world," says a scruffy-bearded man in shirtsleeves and a knit cap on a Brooklyn rooftop. "First, you get up in the morning and you scream!" His mischievous grin melts into something more ethereally content as he screams. At length.

He's had plenty of practice screaming — he does it for a living.

The man is Yishai Romanoff, lead singer of the hassidic punk band Moshiach Oi and one of the half-dozen artists, activists, and culture-makers profiled in the documentary Punk Jews.

The phrase can seem like an oxymoron: The essence of punk is to challenge inherited convention, yet adherence to rich traditions of convention is the common through-line of all of Judaism's myriad flavors.