Share As A Gift

Share a paywall-free link to this article.

This feature is only available for subscribers.

Start your subscription for as low as $4.95. Already a subscriber?

CHUCK COLLINS WAS “born on third base.” As a scion of the Oscar Mayer meat processor fortune, Collins was firmly in America’s top 1%. However, at age 16, he began reading The Catholic Worker newspaper, co-founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin. Within two years he was living with the Mustard Seed Catholic Worker community in Worcester, Mass., serving soup to homeless men. Day’s philosophy of “nonviolent economics” exposed Collins to the violence caused by economic systems. Day believed that there is a “social mortgage on capital” and that society has a claim on private wealth, since it comes from the commons. At age 26, Collins made what he called “the first real adult decision of my life.” He gave away the half-a-million-dollar trust fund his parents had set up for him to local and national groups working for social change.

For 40 years, Collins has organized for a more moral economy. “The prophets, then and now,” he’s written, “call us to a discipleship of equality, working for a society that leaves no one behind, and where all can thrive.” Author of a dozen books, Collins’ newest is Burned by Billionaires: How Concentrated Wealth and Power Are Ruining Our Lives and Planet. He is a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies where he directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good and co-edits inequality.org. He lives in Vermont. Sojourners editor Julie Polter interviewed Collins in September via Zoom. —The Editors

Julie Polter: Most of us think of the ultrawealthy as living in their own world, not about their impact on us and on society’s common good. What do you mean by “the wealthy,” and when do they move from, as you write, buying mansions to buying senators?

Chuck Collins: In the book, I lay out a “Roadmap to Richistan” to describe the different segments of the wealthy. The greatest social disruption is driven by households in the top one-tenth of 1%—that is, those with more than $40 million in assets. Their needs and substantial wants are met, and they’re basically wielding power to distort the rules of the economy—the power to own and dominate. The flow of wealth to this tippy top is the newest chapter of 50 years of pulling apart. In the last 15 years, the lion’s share of income and wealth gains have gone not to the top 1%, but to that one-tenth of 1%. And they are effectively rigging the rules to gain more.

You argue that concentrated wealth and power are ruining the lives of ordinary people in the bottom 99%. How?

I edit a website called inequality.org. A guy, we’ll call Greg B., wrote me a note: “None of my problems exist as a result of someone else being a billionaire.” I wrote him back to say, “I don’t know what all your problems are, but I would suspect a goodly share of them actually are.”

Of course, the barking dog across the street that keeps you awake is not caused by a billionaire. But most problems are caused by an economy that’s tipped in favor of funneling wealth to the top rather than toward a broader shared prosperity.

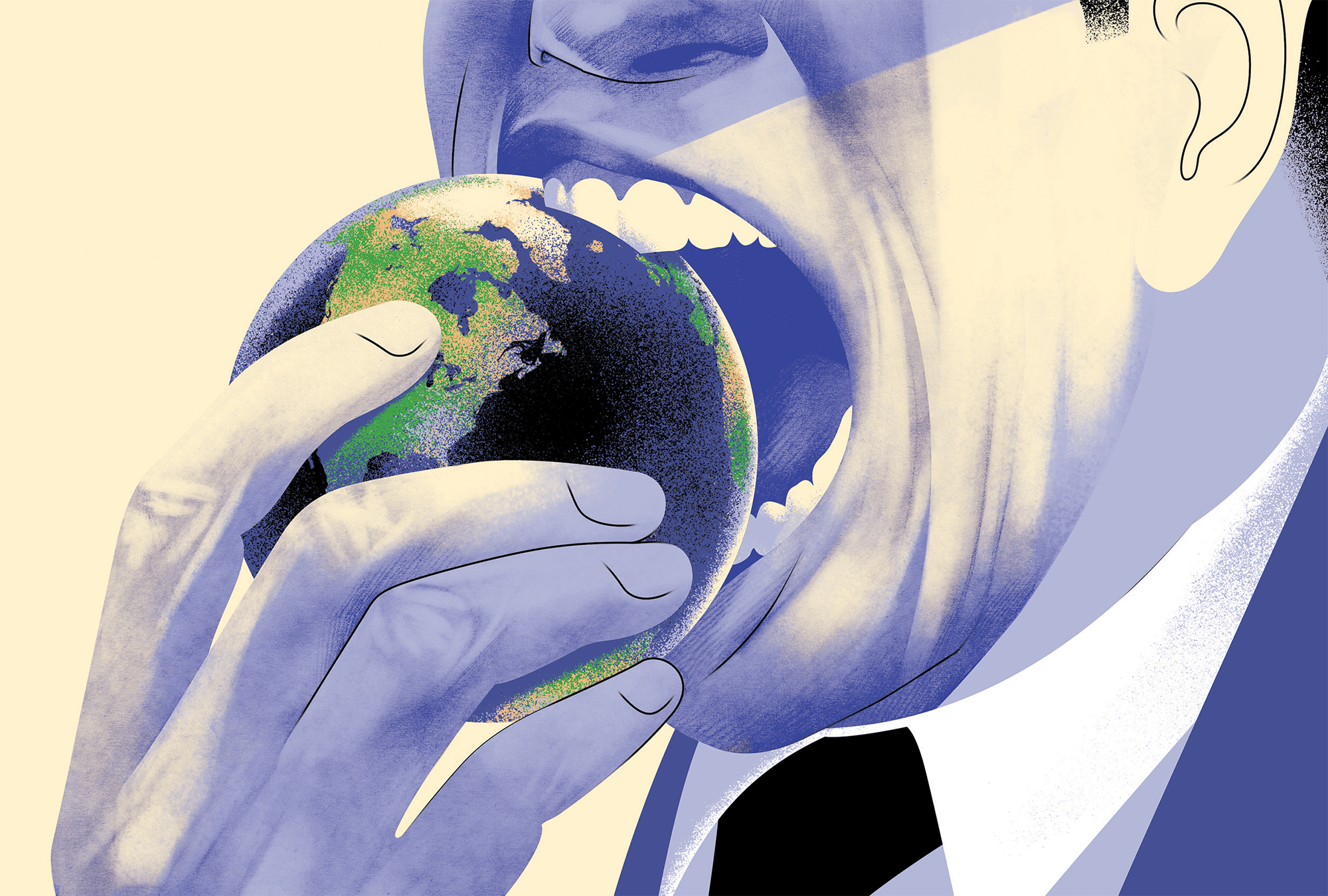

This touches every corner of our lives. Personal health? It’s well shown that extreme inequality is bad for your health. It’s even bad for the health of very wealthy people because it leads to a breakdown of social solidarity and the kinds of things we do together as a society to create healthy communities. Taxes? The fact that billionaires are opting out of paying taxes means everyone else picks up the slack to pay for the public services or else those services weaken, diminish, or go away. Climate change? Billionaires are the super-emitters of carbon dioxide and methane. The fossil fuel billionaires use their power to block alternatives and keep all of us locked in a very bad trajectory.

The greatest social disruption is driven by households in the top one-tenth of 1%.

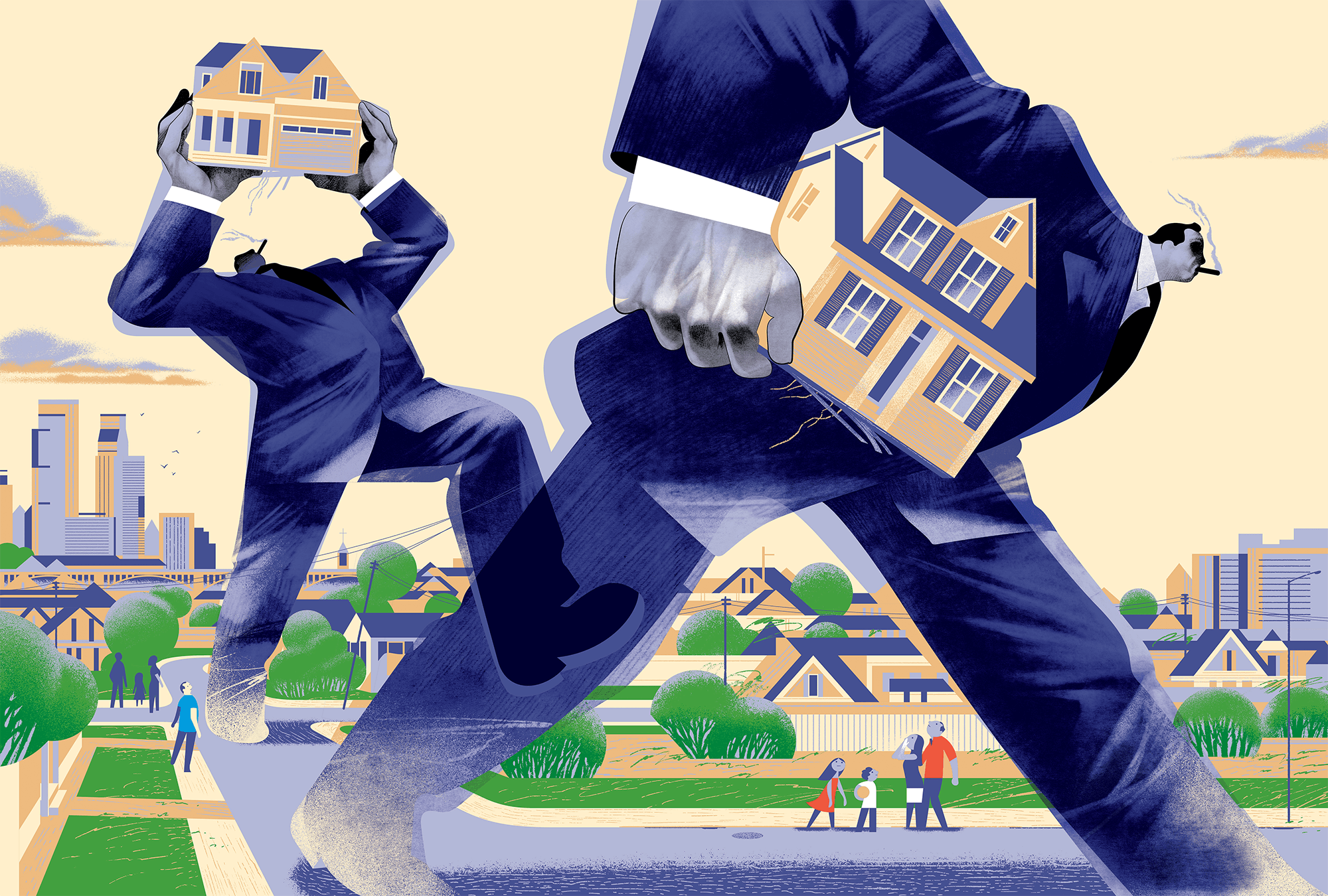

By 2030, you wrote, 40% of single-family homes will be rentals owned by private equity firms and other investors. Why?

This has been a change in the last 20 years. We’ve always had gentrification and wealthy people bidding up the cost of housing, but now it’s supercharged. Billionaire-backed private equity funds recognize that people are stuck in rental housing. This creates an opportunity to extract more wealth from the housing market. Private equity billionaires are buying single-family homes, mobile home parks, and converting traditional rental housing into short-term rentals.

There are neighborhoods in Minneapolis where half the single-family homes on a block have been bought by large investor groups. You might live next door to what looks like a single-family home, but it actually has an absentee owner, a billionaire-owned conglomerate. Jeff Bezos may be your future landlord.

I got my start in New England organizing mobile home tenants to buy their parks as cooperatives. Thank God! Now there are about 160 resident-owned mobile home parks in New Hampshire that are better protected from the wealth extractors. But other states are not so fortunate. One of the mega-millionaire investors said that owning a mobile home park is like owning “a Waffle House where the customers are chained to their booths.” They have to pay what they’re charged.

Are there local policies that could slow Jeff Bezos from becoming our landlord?

A key solution is to tax harmful behavior and invest those taxes in ways that create opportunity for everyone else. One great example in the District of Columbia is the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act and other tools put in place around it. Other states are putting that in place. Another way is to tax luxury real estate transfers of more than $2 million and tax absentee-owned luxury housing. [Experiments in Canada] take the revenue from that tax and create permanently affordable housing or help residents buy the apartment buildings they live in.

Illustrations by André Carrilho

You also write about less obvious intrusions by the billionaire class. How is pet care impacted?

The wealth extractors understand how much we love the animals in our life—and that we’re often willing to go into debt for their care. The Mars family, often associated with candy, is one of the wealthiest dynastic families in America. They moved into the pet space. They’ve bought up veterinary clinics; they’ve bought up pet food and pet care [chains]. Rover.com, the app that connects dog owners to dog walkers, is owned by Blackstone, a private equity company. Blackstone takes a cut every time somebody connects through Rover.com and walks your dog.

A 2024 poll shows that 70% of Americans believe wealth inequality has become a serious national issue. What shifted?

The U.S. has a very high tolerance for inequality, but something happened during the pandemic. People saw billionaires’ wealth accelerate while everyone else became more precarious. The system was rigged so that billionaires got rich, even in a national disaster. People felt preyed upon by the super wealthy.

Most people glaze over when it comes to tax policy, yet it affects everything. What are some game-changing campaigns you’re involved with?

This country has an inheritance tax, the “estate tax,” but it’s so porous as to be ineffectual. Vast amounts of billionaire wealth are transferring from one generation to the next, in the upper canopy of the wealth forest. And it’s not effectively taxed. That’s totally fixable.

There are also global treaties and a movement outside the U.S. to tax wealth and invest in climate transition. The U.S. could rejoin the global minimum tax effort where 130 countries came together to hold corporations accountable to pay a minimum tax.

Our friends at Patriotic Millionaires say that if you earn less than $45,000 a year, then you shouldn’t have to pay federal taxes. Most working people are paying a much higher percentage of their income in local, state, and federal taxes than the top 1% do. We don’t have to become tax experts to know that things are badly out of balance.

Do younger people who’ve only known rising inequality view it differently?

The “decline in social mobility,” meaning that anybody under 45 isn’t going to have the same opportunities as the previous generation, really does touch people. I have three twentysomethings in my family. Every day they ask why they should save money. If I’m never going to have a stable job or own a home, they say, why not just go out to dinner with my friends? But they’re also quick to say that billionaires are blocking their opportunities.

There are two big challenges here. One is the narrative that the rich deserve what they have, plus our internalization of the shadow side of that: “If I’m not rich, then there must be something wrong with me.” The second is a missing sense of agency. I want this book to serve as a pep talk that reminds us that there’s a lot we can do about this!

How are people of faith or religious frameworks changing the narrative around wealth inequality?

Early Christian teaching focused on property ownership, the notion that society has a claim on private property. Those are all Christian ideas. The danger of the idolatry of wealth and the corrosion by wealth to the individual spirit and to the community are fundamental to Christian social teachings.

It’s so interesting that Pope Leo XIV chose the mantle of Leo. The previous pope of that name wrote the 1891 encyclical “Rerum Novarum” [“Of New Things,” on the rights and duties of capital and labor] in response to the first Gilded Age, our previous chapter of extreme wealth imbalance. In a sense the new pope is saying that he’s the pope for this second Gilded Age. He’s going to speak prophetically about the idolatry of wealth worship and the dangers of billionaires and future trillionaires. Pope Leo’s first major interview cited our work at the Institute for Policy Studies on CEO pay and CEOs earning 600 times more than their employees. If wealth is the only thing we value, says Leo, then we’re in big trouble.

All wealth is created in community—with nature and people and workers. No one can say, “I did it alone.” That is the moral basis for taxation: No, you didn’t create your wealth alone. We, as a society, helped create this wealth together through God’s gifts of creation, nature, and the fertile ground we build with our labor and taxpayer-funded investments.

That is a prophetic response to the moment we’re in. The moral measure of an economy is how the “least of these” experience it. That’s how we measure whether the economy is healthy and morally functional. This is a moment for faith communities to talk about how the “billionaire burn” is fundamentally disrupting our common good.

All wealth is created in community—with nature and people and workers.

Illustrations by André Carrilho

In Luke’s gospel, Mary sings, “[God] has brought down the powerful from their thrones and lifted up the lowly; [God] has filled the hungry with good things and sent the rich away empty” (1:52-53). What does this mean to you in light of your work?

I see cracks in the wealth system getting wider every day. Our job is to put our foot in the little crack and help it get bigger. But don’t forget there are human beings inside those wealth-holders who need to be invited home, back to a beloved community of reciprocity and interdependence.

These inequalities undermine everybody’s quality of life—even the very wealthy. We aren’t talking about the bad behavior of individual billionaires, although some behave very badly. But there are also billionaires who are really decent people. I think of Patagonia’s Yvon Chouinard who never wanted to be a billionaire. “That’s not my goal in life. I’ve renounced that,” he said, and gave it all away. Chuck Feeney [co-founder of Duty Free Shoppers Group] lived in a modest apartment in San Francisco. He had $8 billion and gave it away.

These are our siblings who need to be invited back to the table. Not to the head of the table, but to the table. They have gifts and insights for how to create beloved community. We want them in the mix. But people caught in that system, sometimes consciously, use their wealth and power to perpetuate that system and promote narratives that justify inequality. The Patriotic Millionaires are important because they are wealthy people who say that it’s not in their interest—personal or spiritual interest—to allow these inequalities to grow. They say, “People like me should pay more taxes [and] pay a living wage. I should not use my wealth and power to rig the rules to gain more wealth and power.” That renunciation and those role models are important.

It is not a good sign that in 1983 there were 15 billionaires and today there are more than a thousand. The good news is that there are huge cracks in that system among money managers, the younger generation, and people with substantial wealth who are moving toward redistribution in a way that heals the harms caused by wealth extraction.

When I talk to wealthy people, they feel incredibly alone, isolated, and disconnected—like their money is the only thing. Wealth is a disconnection drug. It keeps people apart.

How do you sustain your hope?

In my neighborhood, people have really come together. We have a weekly coffee klatch on Friday mornings where all 30 or 40 neighbors come together. I have a Monday men’s coffee group. I begin and end my week with this sense of neighborliness. There are people who voted for the [current] president in those groups. But it’s a reminder that we live in a place, and we need to be fundamentally neighborly. Don’t let the national narrative dampen what we know to be true about one another: That we are neighbors and we can rekindle our face-to-face community. These are the things that have held humans together through eternity.

Got something to say about what you're reading? We value your feedback!