end times

I HAVE WORKED WITH progressive Christians for a very long time, and I’ve noticed that too much talk about heaven seems to embarrass them.

Many people I’ve encountered have been eager to talk about the gospel of social justice but much less enthusiastic talking about eschatology. They seemed happy, for example, to talk about the feeding of the 5,000, but not so much about the Book of Revelation or the apocalypse.

I have just returned from South Korea where I did an academic lecture on premillennial dispensationalism at Hoseo University. My very basic overview of the five aspects of Premillennial Dispensationalism: tribulational views, millennial views, dispensational categories, the Darby system, and biblical interpretive perspectives created quite a stir amongst students and faculty, which only goes to prove the impact that premillennial dispensationalism has had on the Christian community worldwide. I chose this topic in honor of the recent reissuance of the Left Behind movie.

Since the movie came out on Oct. 3, there have been numerous blog responses. I point you to two in particular that reflect my own views on the details of the biblical text and its interpretation:

- Nobody Is Getting 'Left Behind' (Because the Rapture Is Never, Ever Going to Happen)

- Why ‘Left Behind’ should be... left behind

Given these interpretations of the theology found in the Left Behind series I would like to take the conversation to the next level.

What has not yet been said in any blog that I have read is that premillennial dispensationalism is an elitist theology.

Editor's Note: Spoilers ahead! You've been warned.

Over the past eight episodes of The Leftovers, HBO’s latest drama based on Tom Perrotta’s play of the same name, viewers have been treated to a case study in grief and faith in the midst of a life-changing event. Unlike the Left Behind series, which incorporated Christian triumphalism with terrible theology, The Leftovers examines the deeper human and spiritual issues of what would happen were two percent of the population to suddenly disappear. It is powerful and beautiful and really hard to watch (especially Episode Five). It asks the question: does life go on when your world is changed forever?

The show offers a variety of responses to the Sudden Departure of October 14: Kevin Garvey, the police chief who seems to be losing his mind after his wife leaves him for a cult and after his father needs to be committed; Nora Durst, who’s lost her entire family, so she keeps everything exactly as it was when the Sudden Departure occurred; Rev. Matt Jamison, Nora’s brother whose faith has been shaken because he was not taken; the town dogs who have become feral; and finally, the creepiest citizens of Mapleton, the Guilty Remnant, or the GR as they’re “affectionately” known.

This past week’s episode gave us a greater understanding of the GR. Although the nihilistic views of the Guilty Remnant are quite different from those of Christianity, I was struck by their powerful and strategic mission of witness. The cult was formed out of the recognition that everything changed on October 14 and that to pretend otherwise was foolish. The group, in their white clothes, their silence, their stripped-down existence, bears witness to the fact that they are living reminders of what happened. They are fundamentalists about their cause and willing to die for it — even if that death comes from their own hands.

Could a series of “blood moon” events be connected to Jesus’ return? Some Christians think so.

A string of books have been published surrounding the event, with authors referring to a Bible passage that refers to the moon turning into blood. “The sun shall be turned into darkness, and the moon into blood, before the great and terrible day of the Lord,” Joel 2:31 says.

For thousands of years, select groups of Christians have thought their generation was Earth’s last. Even the Apostle Paul thought Jesus would return in his lifetime. But Paul didn’t have the audacity to pinpoint an exact date for what we call the Rapture. Harold Camping, on the other hand, did.

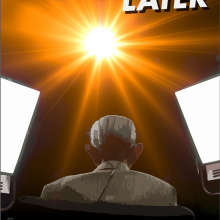

Apocalypse Later: Harold Camping vs. The End of the World a new documentary that premiered June 8 — exposes wrongful and conflicting beliefs about Jesus’ return by sharing Camping’s concrete opinions of those who didn’t follow his beliefs of the apocalypse. Declaring their spot in hell, Camping was certain that those who didn’t follow his apocalyptic views would spend eternity in damnation.

Apocalypse Later tells the story of Camping, a man who had to let go of his pride and face the reality of joining the dozens of others who have wrongly predicted the end of time.

In the documentary, historian and New Testament scholar Loren Stuckenbruck refers to the apocalypse as a “literary genre,” a “mode of thought,” and “a social movement.”

The film is emotional and shocking, contrasting the scary, more literal interpretations of fundamentalist Christians with the more nuanced hermeneutical approaches of academics like Struckenbruck. The juxtaposition reveals that the tensions and battles that Christians face might not be against those who will be “left behind,” but rather between Christians themselves.

The Jews believe that the Messiah is yet to come.

Christians believe the Messiah is coming back.

Those of other – or no – religions haven’t noticed much difference and don’t really care.

But all would agree that there is plenty of work left to be done.

We, by any standard, are far from an age of any Messiah — an era of justice, peace, and restoration seems as distant or alien or even incomprehensible as a blockbuster sci-fi film.

But perhaps, in some odd way, that is the point.

We in our era have accomplished something no other civilization would have considered possible — or desirable. We have taken human wastefulness and self-destruction to never-before-seen levels and we have distorted our scriptures to justify even celebrate — our own destruction.

Whether it is fracking (with its own legacy of toxic waste) the Keystone XL Pipeline (with its virtually guaranteed oil spills across prime farm land) accompanied by the largest population ever seen on the face of the earth — with its attendant garbage and sewage — we are seeing threats to our climate, food supply, economy, and quality of life on a level never seen before in human history.

Historically, theologies (and philosophy) have put a brake on human avarice, violence, and unbridled destruction of the environment.

Reflection and restraint, for millennia, have been the twin pillars of historic conservatism.

Not now.

I WAS BROUGHT UP up on stories of my family's emigration to Russia from England in the 1850s and of the three generations we lived there and intermarried. My grandparents fled the upheavals of revolution in 1917, returning to England. Having drunk deeply from the springs of Russian spirituality, it is second nature to me to hear the scriptures with Russian ears. As Eastertide culminates at Pentecost (rounded out in the wonderful coda of Trinity Sunday), I find myself murmuring as a mantra the great injunction of St. Sergius of Radonezh, "Beholding the unity of Holy Trinity, to overcome the hateful disunity of this world!" The doctrine of the Trinity is no mere antiquity, but a beacon pointing to the future that God desires for the world. In the Trinity, "hateful disunity" can be transformed into life-in-communion; our life together as human beings incarnating our identity as ones made into the image and likeness of God. I will find myself doodling on my notepad the provocative claim of the Russian lay theologian Nikolai Fedorov: "Our social program is the dogma of the Trinity."

Taking in again the Trinitarian grammar of our prayer and faith, I will find myself reinvigorated for the task of forging a spirituality that, as a great Anglican priest Alan Ecclestone wrote, "takes its Trinitarian imagery more seriously than ever before, relating the creativity, the humanizing, and the unification of [humankind] in one growing experience of mutual love." This from a man who was a passionate political activist writing from the thick of gritty urban politics, not from an ivory tower.