Selma

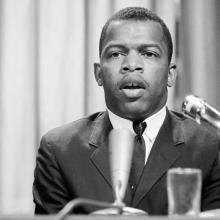

On Jan. 13, Georgia Rep. John Lewis — civil rights icon who was beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., marching for voting rights for African Americans in 1965 — said he would not be attending President-elect Donald Trump's inauguration, a first for the longtime congressman since serving. Trump took to Twitter the morning on Jan. 14 to attack Lewis.

Left to right, Nate Powell, Rep. John Lewis, and Andrew Aydin. Image via Sandi Villarreal / Top Shelf Productions / RNS

Q: Representative Lewis, in an earlier book of this series we read that you were asked by church leaders to tone down your speech at the 1963 March on Washington. How does March: Book Three deal with issues of faith?

Lewis: Book Three tells a story how people kept going, how people never gave up or gave in, in spite of the bombing of a church, the beating on the bridge as we had left church to march all the way from Selma to Montgomery. We kept going, we never gave up, we never gave in, we never became bitter or hostile. We kept the faith. It was the music of the church that lifted us, that carried us. … We felt like God Almighty was on our side.

John Lewis. Image via Marion S. Trikosko / Library of Congress

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum will give its highest honor to a lion of the American civil rights movement, U.S. Rep. John Lewis, D-Ga.

Lewis will be presented with the Elie Wiesel Award at the museum on May 4. Chairman Tom A. Bernstein lauded Lewis in a statement as a leader of “extraordinary moral and physical courage” and “an inspiration to people of conscience the world over.”

Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala. James R. Martin / Shutterstock.com

We live in a culture that not only glorifies violence, but often celebrates its use against the “enemy" as the truest form of heroism and bravery. While I won’t get into the debate of whether violence is ever justified to preserve life (a much bigger conversation extending far beyond an 700-word post), I will say I’m deeply troubled by our assumption that violence is the only way to respond to a real or perceived threat.

Jim Wallis is determined to bring ongoing conversations about race in America to his fellow white Christians.

“If white Christians acted more Christian than white,” he writes in his latest book America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America, “black parents would have less to fear for their children.”

Below, you can watch the trailer for the book, which focuses on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., where hundreds of civil rights demonstrators were attacked by armed policeman in 1965.

I enjoy cop shows on television.

My favorite is Blue Bloods, following the “Reagan” family from terrorist threats to homicides to domestic violence.

I can’t imagine what it’s like to be a cop. Perhaps routine marked by bursts of frenzy, some of it life-threatening. One’s hometown seen through the lens of crime, tragedy, and evil. Low pay, high risk.

I like Blue Bloods because it shows upright law enforcement taking “Protect and Serve” seriously and making brave and ethical choices.

These shows are quite unrealistic, of course. Crime doesn’t get solved that easily or snap decisions made that wisely.

I don’t think, however, that I realized until recently how separated from reality those fictional accounts have been. As police shootings of unarmed citizens go viral, as minorities talk of long-standing police brutality, as we watch guards beating prisoners, and as federal law enforcement engages in creepy surveillance, internal corruption, and the arming of local police as military commandos, the veil is lifted.

Now we see in our own American law enforcement the same brutality and power-madness that have marked corrupt societies we supposedly surpassed, from the secret police in Eastern Europe to uniformed thugs in South America.

I find it confusing. Not the discovery that TV isn’t real, but to see how low we have fallen. Has this brutality been the dark side of police work all along?

"We do not see things as they are. We see things as we are.” This Talmudic quote from Rabbi Shemuel ben Nachmani notes that seeing is not always vision. What we see in life is more than what the eye beholds. A person or circumstances right in front of us can be merely the surface of someone or something more profound.

The United States must forever recall the struggles, moves, and marching of the women and men across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Fifty years ago, ordinary people walked for the right to stand up and be counted. To the naked eye, those sojourners lacked political clout as much as they did fiscal wherewithal. Those citizens were not persons of means, but their intentions were good. They meant well. They meant to do whatever — to get the right to vote.

No whips, dogs, horses, or hoses would stifle their efforts. The Americans who marched from Selma to Montgomery may not have looked like much, but their actions changed this country’s political horizon and racial landscape. Yes, a yearning in their loins propelled them to create social change. They were going to vote at any cost, at any price.

In this week’s lectionary passage, a man crippled from birth wanted “change.” Actually, he wanted coins or any alms that Peter and John could offer (Acts 3:1-11). To this man, the two disciples were in better shape than he was. From his view, he could surely benefit from whatever they had to offer. Yet, Peter exposes their impecunious state: “Look on us. We don’t have a nickel to our names.”

There was nothing spectacular or dazzling about Peter or John.

Last month I traveled to Selma, Ala., to commemorate the anniversary of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches. Fifty years ago, images of the “Bloody Sunday” brought the horrors of racial terrorism into the living rooms of the American public, as brutal images of marchers left bloodied and severely injured dominated the evening news. As a young African-American clergywoman and interfaith organizer, I am the fruit of the labor of civil rights pioneers in places like Selma, Ala., Greensboro, N.C., and Jackson, Miss. Today, the work continues through the organizing and activism of young people across the country catalyzing a 21st century interfaith movement for civil and human rights.

On April 14, I will join together with many of these young leaders in celebration of Better Together Day. An initiative of Interfaith Youth Core, Better Together Day amplifies the power of interfaith cooperation as a tool for positive social transformation.

This year participants are encouraged to have a conversation with someone with a different moral and ethical belief system than their own as a means of breaking down barriers and combatting bias. Research shows that when people get to know someone different from them, their sentiments toward that entire group shift for the positive. Put simply: Our biases decrease when our encounters with “the other” increase. The event could not come at a more timely moment. The headlines of major newspapers over the past 12 months, from the killing of three Muslim students in Chapel Hill, N.C., to the rise of the #blacklivesmatter movement, show that there is much work to do in confronting bigotry and systemic oppression in our nation.

I experienced the transformative power of interfaith encounter and exchange firsthand in the fall of 2009. Fresh out of college, I took a 6-month position as community organizing fellow at a small food justice organization in Nashville, Tenn. My assignment was to support a new campaign designed to engage religious communities as advocates in food deserts — communities with little to no access to affordable, healthy food. New to the South and to the working world, I arrived my first day with a stomach full of butterflies and anxiety. A woman with dark curly hair and slight Southern drawl greeted me at the door and my nerves immediately subsided. Her name was Miriam, and in a few short months, she would change the course of my life.

The Edmund Pettus Bridge was named after a Confederate general who became a Grand Dragon in the Ku Klux Klan. His name, still emblazoned over the top of that now famous bridge, was a powerful and threatening symbol of white power and supremacy in Selma, Ala. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had at one time removed Selma from their list of places to organize because “the white folks were too mean, and black folks were too afraid."

But that didn’t deter a group of courageous African Americans from marching across that bridge a half-century ago, risking their lives for the right to vote in America. They were attacked and beaten by the fierce forces, led by notorious Sheriff Jim Clark, for their resistance to the frightening violence of white power.

Last Saturday, during the 50th anniversary event of “Bloody Sunday,” I spent many hours just looking at that bridge. The words that kept coming to me were “courage” and “resistance.” My question became: what bridge we will now have to cross?

Congressman John Lewis, whose skull was cracked that day as a young man, opened the main event.

"On that day, 600 people marched into history … We were beaten, tear gassed, some of us [were] left bloody right here on this bridge. … But we never became bitter or hostile. We kept believing that the truth we stood for would have the final say.”

Then Lewis introduced the president, "If someone had told me, when we were crossing this bridge, that one day I would be back here introducing the first African-American president, I would have said you're crazy.”

What happened on this bridge, President Barack Obama said, “was a contest to determine the meaning of America,” and where “the idea of a just America, a fair America, an inclusive America, a generous America … ultimately triumphed.”

The white ministers didn’t fly down to Alabama in January, when Sheriff Jim Clark clubbed Annie Lee Cooper outside of the county courthouse, nor in February when a state trooper fatally shot twenty-six-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson in the stomach for trying to protect his mother after a civil rights demonstration.

But on Bloody Sunday everything changed. At 9:30 p.m. on March 7, 1965, ABC news interrupted a broadcast to show hundreds of black men, women, and children peacefully crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge toward Montgomery and a sea of blue uniforms blocking their way. The marchers were given two minutes to disperse, and then the screen filled with the smoke of tear gas, police on horseback charging the screaming crowd, burly troopers wielding billy clubs and bullwhips, a woman’s hem rising up over her legs as a fellow marcher attempted to drag her away to safety.

Overnight the nation’s eye turned toward Selma. Rev. Martin Luther King sent a telegram to hundreds of clergy that Monday, urging them to leave their pulpits and join him in Alabama to march for justice. Some supporters, like the reporter George Leonard, packed their things immediately after watching the newscast from Selma.

“I was not aware that at the same momemt ... hundreds of these people would drop whatever they were doing,” Leonard wrote later.

“... That some of them would leave home without changing clothes, borrow money, overdraw their checking accounts, board planes, buses, trains, cars, travel thousands of miles with no luggage, get speeding tickets, hitchhike, hire horse-drawn wagons, that these people, mostly unknown to one another, would move for a single purpose to place themselves alongside the Negroes they had watched on television.”

Selma changed the course of history by paving the way for the passage of the Voting Rights Act, but its impact didn’t end there. The spirit of Selma rippled outward, forever changing those who made the long journey to Alabama — including a white minister from Washington, D.C., named Rev. Gordon Cosby.

With the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday this weekend, America was reminded how this small city helped bring sweeping change to the nation.

But while Selma might have transformed America, in many ways time has stood still in this community of 20,000 that was at the center of the push that culminated with the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Dallas County, of which Selma is the county seat, was the poorest county in Alabama last year. Selma has an unemployment rate of 10.2 percent; the national rate is 5.5 percent.

More than 40 percent of families and 67 percent of children in the county live below the poverty line. The violent crime rate is five times the state average.

The Birmingham News called the region, known as the Black Belt because of its rich soil, “Alabama’s Third World.”

The images of that day in 1965 were quickly seared into the American consciousness: helmeted Alabama state troopers and mounted sheriff’s possemen beating peaceful civil rights marchers in Selma, Ala., as clouds of tear gas wafted around the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

On March 7, 1965 — a day that would become known as “Bloody Sunday” — 600 marchers heading east out of Selma topped the graceful, arched span over the Alabama River, only to see a phalanx of state and local lawmen blocking their way on U.S. Highway 80.

The police stopped the marchers, led by Hosea Williams of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and John Lewis, chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and ordered them to disperse. Then they attacked. Lewis, one of 58 people injured, suffered a skull fracture. Amelia Boynton Robinson, then 53, was beaten unconscious and left for dead, her face doused with tear gas.

Photos of that terrible day were seen around the world. Historians credit the beatings, and the public outrage that followed, as a catalyst for the passage of the Voting Rights Act.

FOR TWO YEARS in a row we have seen significant films about oppression and struggle nurture public consciousness. Selma and 12 Years a Slave invite us to reimagine iconic moments closer than we usually think, their protagonists more like us. Slavery had not been portrayed in such visceral fashion in a mainstream film before 12 Years. Before Selma, images of Martin Luther King Jr. had never quite transcended the almost superhuman projections that accrue from his martyrdom and decades of being co-opted by cultural mavens from Apple to Glenn Beck.

These films create new benchmarks for the mainstream depiction of black history, black struggle, and wider perceptions. But entertaining portrayals of inspiration contain a powerfully dangerous substance that needs to be handled with care. The cathartic tears shed at a film about other people’s suffering and heroism can also be a narcotic, implying that the work has been done. Think of all the talk about freedom struggles after Braveheart, or challenging the principalities and powers after The Matrix. The problem was, most of it was just that. Talk.

The journey to end systems of injustice begins with a single step. This theme resonates throughout the recently released film Selma, which recounts the events leading up to the famous Selma-to-Montgomery march. Led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., this march catalyzed the full enfranchisement of people of color through the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The Voting Rights Act is considered to be one of the most successful achievements of the civil rights movement. But 50 years later, the residue of Jim Crow laws that banned people of color from voting lingers today in a new, subtle form: disenfranchisement laws for people with felony convictions.

Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow, examines how these laws strip minority communities of their voice in the public sphere because of the disproportionately high percentage of racial minorities “swept into” America’s mass incarceration system.

Last night I watched the State of the Union, because I live in D.C., and this is our Super Bowl. My roommate, who works on women’s rights, was listening for any mention of her "issues." And I’m no different: I tuned in to the president’s address to hear what he would have to say about climate change.

And he did have a lot to say! This is what he said:

"And no challenge — no challenge — poses a greater threat to future generations than climate change.

"2014 was the planet’s warmest year on record. Now, one year doesn’t make a trend, but this does — 14 of the 15 warmest years on record have all fallen in the first 15 years of this century.

"I’ve heard some folks try to dodge the evidence by saying they’re not scientists; that we don’t have enough information to act. Well, I’m not a scientist, either. But you know what — I know a lot of really good scientists at NASA, and NOAA, and at our major universities. The best scientists in the world are all telling us that our activities are changing the climate, and if we do not act forcefully, we’ll continue to see rising oceans, longer, hotter heat waves, dangerous droughts and floods, and massive disruptions that can trigger greater migration, conflict, and hunger around the globe. The Pentagon says that climate change poses immediate risks to our national security. We should act like it."

What struck me was that it’s now totally normal for the President of the United States to speak firmly and at length about the clear and present danger of climate change.

Look at how far we’ve come! This is real progress — this is a cultural shift. This is a victory.

But this Monday, I marked Martin Luther King Day by reading the Letter from a Birmingham Jail with members of a neighborhood church. And I heard Dr. King admonishing me for my celebration.