book review

FIFTEEN YEARS AGO, Richard Florida argued in The Rise of the Creative Class that cities fostering brainy interaction, creativity, and innovation would thrive, since modern capitalism was increasingly knowledge-based. His projections were acclaimed by artsy, back-to-the-city types (including many church planters) and scorned by activists and the low-income residents that gentrification displaced.

The critics were on to something, because since then many big cities have indeed gotten sexier, but not necessarily more reliable, especially for the masses. From 2006 to 2014, average incomes declined by 6 percent, while average rent prices soared by 22 percent. Today, about 21 million American renters are putting 30 to 50 percent of their income toward rent, with 30 percent representing the “cost-burdened” threshold.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. did not initiate black prophetic preaching; he was, rather, initiated into it. Rev. Kenyatta Gilbert’s A Pursued Justice: Black Preaching from the Great Migration to Civil Rights is a theological origin story about the distinctive rhetorical tradition that is black prophetic preaching.

The text begins by naming the social crisis of the Great Migration—shorthand for a massive demographic shift of 1.5 million African Americans from the South to the North between 1916 to 1940—as an essential context for understanding black prophetic preaching. This tradition of Christian proclamation—which Gilbert calls “exodus preaching”—is framed in the context of black pastors seeking to respond theologically to the pressures of injustice, prejudice, and segregation that black migrant workers navigated in Northern urban communities in the inter-war period. Of special note, Gilbert surfaces the social gospel tradition of African-American clerics who, unlike white social gospel leaders Walter Rauschenbusch, Josiah Strong, Washington Gladden, and others, demonstrated a desire to not only build institutional churches that confronted industrial evils but also to address systemic issues of lynching, police brutality, and so on.

While the entire book makes an important contribution to the study and practice of preaching, the third chapter, in particular, sparkles with insight. Within it, Gilbert marshals a solid cast of intellectuals—including Paulo Freire and Zora Neale Hurston—to land on a four-part definition of prophetic preaching. He contends that prophetic preaching unmasks systemic evil, remains hopeful in difficult situations, aids listeners in naming their own reality, and displays a will to adorn. The criterion of adornment—with patient attention to aesthetic categories of beauty, vision, and desire—is some of the most creative theological writing, in any genre, that you are likely to read. On a practical level, the definition provides a yardstick against which working preachers and homiletics faculty can assess the strength of contemporary pulpit work.

I LEARNED HOW to bike relatively late in life. I was 23, and it cut my commute in half. Since I’d been walking an hour each way for a night shift that started at 11 p.m., that meant a lot. My guru was an elder from my local church who lived across the alley. He taught me how to change a tire, gears, and my life. He showed me hospitality by teaching me about my bike, but it extended much further than that.

UCC minister Laura Everett does much the same thing in Holy Spokes . She uses the metaphor of a bike as a lens to discuss the broader issues of how to relate to people, the Earth, and God: Mostly how, to use Brother Lawrence’s term, to practice the presence of God.

IN 1967, I TRAVELED with activist friends from New York to Baltimore to support four people there who poured blood on the 1A files that compelled young men into the military and the massacre in Vietnam. The “Baltimore 4,” as they became known, committed the first of some 100 actions focused on draft boards, the source of cannon fodder in the ever-escalating wars in Indochina. It was during one of these trips that I met Willa Bickham and her husband, Brendan Walsh. Our friendship has been rich, varied, invaluable.

In The Long Loneliness in Baltimore, Walsh and Bickham tell of their nearing 50 years serving the people of Baltimore as the Viva House Catholic Worker. It is a story that needs telling, especially now in this country that is profoundly ruptured by economic and racial conflict.

Try as the politicians and the press might, it is impossible to disengage economics from race. Bickham and Walsh know this intimately, living in the midst of an impoverished black neighborhood. They have experienced drugs, murders, robberies, and destruction right outside their front doors. The alley that runs beside their home, thanks to their creativity, is marked with memorials to men and boys shot and killed there. Repeatedly, after almost every major killing, Walsh has told the press what has become crystal clear to him: that in Baltimore City (as in too many cities), selling drugs is the only job that exists for all-too-many people of color.

In the garden outside Viva House is the Hope Stone. In Bickham’s script, it quotes Martin Luther King Jr.: “We will hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.” That is the invitation to all who come to Viva House for whatever reason, to meet whatever need. Each is sure to receive respectful and caring human interaction, food, fellowship, help with bills, a place to escape the cold or heat or rain, a place of justice and peace.

AS A TEENAGER growing up in a church setting that discouraged engaging with movies, books, or music deemed a “bad influence,” I remember frequently being confused about pop culture, particularly when it came to what films I was “allowed” to watch. Was I wrong for wanting to see Taxi Driver ? For identifying with Saved? Was it a sin to watch The Last Temptation of Christ?

The answer to all these questions, of course, is “no,” but the sentiment behind them is understandable. The easiest metric for Christians to judge a film’s quality is the measure of its “objectionable” content, regardless of what that content says about the filmmaker’s intent, or the political or cultural attitudes under which it was conceived. The truth, however, is that all art—whether spiritual or secular in origin—has something to express about the world: joy in its beauty, anger at its injustice, a whole spectrum of emotions and ideas that reflect the human experience.

Viking Economics: How the Scandinavians Got it Right — And How We Can, Too, by George Lakey. Melville House.

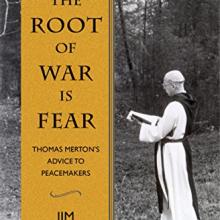

DO WE LIVE in a post-Christian era? Catholic monk Thomas Merton thought so, back in 1962, when his anti-war book Peace in the Post-Christian Era was banned by monastic censors.

He would surely come to the same conclusion today, when we hear a pulpit Christianity still identified with war and nationalism and listen in shock to a new U.S. president woefully ignorant of the peril of nuclear war. Our deeply divided nation holds scant promise for peace in our streets or in the world, despite the growing chorus of Christian peacemakers.

This new book by Jim Forest adds both deep compassion and timely advice to that chorus. The wise words of Merton, who served unofficially as “pastor to the peace movement” during the Vietnam War, are needed now more than ever. Clearly titled chapters quote from Merton’s published writing as well as his letters to Forest and other peacemakers.

In October 1961, The Catholic Worker published Merton’s essay “The Root of War is Fear,” and Merton ran afoul of monastic censors. He was eventually silenced publicly but fortunately was allowed to circulate Peace in the Post-Christian Era in mimeographed form and to continue writing letters, although for several years everything passed through the censor’s hands. One of the delights of this book by Forest is the first publication of an uncensored and scathingly sardonic letter Merton wrote under the pseudonym “Marco J. Frisbee.”

“A SUGGESTION: Speak much about Jesus.” Henri Nouwen’s recommendation to a friend, captured in Love, Henri—a new collection of his personal correspondence—encapsulates the priest and author’s private and public ministry. More than almost any other modern figure, Nouwen bridged Catholic/Protestant doctrinal divides with his writing to bring spiritual healing and comfort, even as he wrestled with what he termed his inner “demons.”

Edited by Gabrielle Earnshaw and released in conjunction with the 20th anniversary of Nouwen’s death, Love, Henri highlights the priest’s struggle for inner peace and his extensive web of deep friendships. While the collection does not present any shocking revelations, and contains fewer transcendent moments of raw emotion than other collections of Nouwen’s writing, it works well as a meditation on what it means to love selflessly and extend oneself over a lifetime.

In the collection, Henri is both protagonist and antagonist, healing and wounding those in his life. While Nouwen himself acknowledges “a kind of enthusiasm” in his own writing that “seems a little bit too easy,” the gift is watching him participate in these seeker/giver relationships. In early letters, he is often overly attached: “Maybe your distance simply means that I force myself upon you and there is not a mutuality that makes friendship possible.” Later, though, we see him “speak about [his] inner struggles as a source of self-understanding” and solidarity, rather than a way “to avoid difficult positions and responsibility and evoke some sympathy.”

IN DOROTHY DAY: The World Will Be Saved by Beauty, author Kate Hennessy, Dorothy Day’s youngest granddaughter, gives a deeply intimate and highly credible account of her grandmother, a writer, social activist, and co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement with Peter Maurin in the 1930s. Hennessy explores themes of integrity, vocation, and community, portraying Dorothy Day honestly in her gifts and faults. But the most powerful thread is raw beauty that links together the author to her grandmother, strangers to one another, and people to God.

Day’s life was often complicated and marked by loss. Nonetheless her worldview was postured toward the words of poet Max Bodenheim: “I know not ugliness. It is a mood which has forsaken me.” Queen Anne’s Lace growing in the city, spinning wool with her grandchildren, her love for the father of her only child, standing in a breadline with seamen, or walking along the shore are all examples of the beauty that both guided and followed Dorothy Day.

Day, who was born in 1897, wasn’t yet a Catholic when she moved to New York City from Illinois in 1916 in pursuit of a writing career. She mingled with writers, artists, and radicals and was active in the social movements of the time. Hennessy notes that Day “was not always the clear-eyed visionary that we now see her as.” Day considered her life “disorderly” and moved from job to job, from one lover to another; she tried to commit suicide on two different occasions.

But even before Day knew God, she knew that God was leading her. She said, “I cannot help my religious sense, which tortures me unless I do as I believe right.”

THIS IS A PRE-TRUMP book with serious questions for our politics in the age of Trump.

A political memoir from Michael Wear, a young evangelical strategist who worked in Obama’s faith office, it tells stories from the fights of those years and offers a vision of a future faith-in-politics.

I’m a sucker for this kind of memoir: a chastened idealist tells how people worked well together. His ideals have met reality, but Wear still believes politics can help people.

More than merely telling old war stories, Reclaiming Hope makes a sustained case for public service. It argues well that Christian love should motivate us to become active within existing political institutions. Wear highlights specifically race and religious freedom as fields needing further work (a great combination, designed to irritate people all across the ideological spectrum). We need to figure out how to live together and build cultures that respect people and enable them to live without fear.

Although Wear avoids cynicism (and criticizing his former coworkers), his time in high-level politics did chasten him. His reflections on the contentious religious issues raised during his Obama administration tenure, particularly abortion, the contraception mandate, and marriage equality, although only comprising a portion of the book, raise necessary questions for any local or national progressive coalition.

THE MERE MENTION of maras—gangs that formed in the U.S. and then spread throughout Central America—conjures up overcrowded prisons filled with ominous-looking, elaborately tattooed Central American youth flashing gang signs. While this reality does exist, it’s part of what German scholar Sonja Wolf calls a folkloric attempt to demonize disenfranchised sectors of society rather than invest in comprehensive social programs.

Her new academic book, Mano Dura: The Politics of Gang Control in El Salvador, offers a far deeper analysis of public policy. It’s a must-read for any aid worker or missionary hoping to build peace and prosperity in a country with one of the highest homicide rates in the world—81 homicides per 100,000 people, eight times the U.N.’s marker for an epidemic. It also raises important questions about how much violence can actually be attributed to gangs when crime data is patchy and politicized.

The book, an updated version of Wolf’s 2008 doctoral dissertation in international politics, examines two decades of attempts to “pacify” El Salvador’s gangs, a subculture that diversified and expanded after El Salvador’s 1992 U.N.-sponsored peace accords. During the 12 years prior, a civil war claimed some 75,000 lives and prompted 1 million Salvadorans to seek refuge in the U.S. Some of these young refugees joined large U.S. gangs such as 18th Street or created their own, such as MS-13, then brought their gang affiliation back to El Salvador during mass deportations in the early 1990s.

JIM SANDERS IS among the most respected and influential world-class Old Testament scholars of the last (my) generation. His signature interpretive impulse is what he calls a “monotheizing process.” By this Sanders means an urge toward affirmation of and obedience to the one true God, an affirmation and obedience that issues in love of the enemy in a way that requires dialogic engagement. By the term “process” Sanders insists that “monotheizing” is a dynamic, ongoing act that never reaches closure but always invites new energy and imagination. Thus, one can find in Sanders’ work both large-hearted energy and passion.

The present book is a narrative account of his life, attentive to two important themes. It traces Sanders’ maturation as a scholar with a teaching career at Colgate Rochester Divinity School, Union Theological Seminary, and Claremont School of Theology. Sanders’ great scholarly work has been his generative contribution to textual matters, with an initial focus on the Dead Sea Scrolls and then work at the Ancient Biblical Manuscript Center in Claremont, Calif., where he was the key figure.

That scholarly maturation is matched in the narrative by an account of how Sanders has emerged as a powerful and insistent advocate for social justice. In his telling he grew up in South Memphis in a community that practiced racial apartheid with what he terms an “iron curtain” between whites and blacks, reinforced by an evangelicalism of the privatizing kind.

The turning point for Sanders was his college and seminary experience at Vanderbilt University. He has very little to say about his formal study in those degree programs. What counts in his memory is his involvement in campus Christian ministry programs where he came to understand the urgency of social ethics that forcefully summoned him beyond his initial evangelicalism. Led by good mentoring, he discerned the systemic practice of injustice that contradicted his newly aware sense of the gospel.

FOR DECADES, pastor, activist, and scholar Bill Wylie-Kellermann has kept alive and furthered a theology of the biblical “powers and principalities” (Romans 8:38; Colossians 1:16; Ephesians 6:12), in the tradition of William Stringfellow and Walter Wink. Principalities in Particular is a compilation of his essays, rooted in applied struggle and practice, on these invisible but embodied forces that shape and often dominate human life.

Through stories of engaging specific principalities over time, Wylie-Kellermann brings an abstract concept to life. He explores racism, nuclear weapons, sports, family systems, corporate globalization, slavery, the drug powers, war, the Trump presidency, the global economy, and other principalities, immersing readers in a worldview that perceives not only their outer manifestations, but their inner realities as well.

One example is the corporate-friendly system of emergency management that has replaced democracy in controlling the author’s home city of Detroit and other black-majority cities in Michigan.

Wylie-Kellermann portrays local community struggles as fighting (nonviolently) for the soul of the city. He describes a statue called “The Spirit of Detroit,” which stands near City Hall, providing a focus and gathering place for community activists. In a similar vein, he tells of an interfaith group that drafted letters to “The Angel of Detroit,” calling the city back to its better nature and true vocation in service of life.

Wylie-Kellermann claims that “half of any struggle is a spiritual battle.” What is at stake is not simply a specific desired outcome, but also human healing and liberation. “We are complicit in our own captivity. ... The healing of the planet and the healing of ourselves, inside and out, are one.”

THIS BOOK SURPRISED me. Millennials and the Mission of God incarnates the “prophetic dialogue” of the subtitle. There are many books about millennials, but here a representative speaks for herself and an older interlocutor listens and responds to the concerns and arguments voiced. Together, baby boomer Andrew Bush and millennial Carolyn Wason ponder the future of the church, how Christianity is changing, and how to engage millennials.

Those with no affiliation, the Nones, are growing; traditional ministry models are failing. Wason, with her background in anthropology, sheds light on why. Her prose is playful and filled with self-deprecation as she laughs at her generation’s idiosyncrasies. As she muses on hashtag activism and Harry Potter, she is frank, openly discussing the role fear plays in millennial evangelism. The long history of Christians oppressing people of other faiths weighs heavily on the shoulders of this emerging generation. Afraid of unconsciously leveraging an ill-gotten Christian privilege, many millennials retreat from traditional evangelizing.

For Wason, the question of faith is not “Is it true?” but rather, “Does it matter?” Thus, her doubts and questions center not on the Bible’s veracity, but on the influence of the church on the world. Her observations will resonate with many millennials.

IT FEELS GOOD to laugh out loud. In the past year I haven’t felt lighthearted about weighty topics such as our political leadership, globalization, and climate change. But Bill McKibben’s latest book, Radio Free Vermont, reminds me that humor can be as powerful as protest in speaking truth to both injustice and abuse of power. Prolific writer, climate organizer, Sojourners columnist, and co-founder of the organization 350.org, McKibben has given his life to galvanizing the climate movement. He advocates for a diversity of strategies, from a carbon tax to public art, with a seriousness reflecting the high stakes of inaction. In his first work of fiction, the satirical plot of Radio Free Vermont revolves around the exploits of Vern Barclay, a 72-year-old radio announcer who finds himself at the center of a campaign to convince Vermonters to secede from the U.S. His motley crew of allies includes Perry Alterson, a teenager with technological expertise who ends every sentence with a question; Trance Harper, a former Olympic biathlon winner; and Sylvia Granger, a firefighter who harbors these fugitives while teaching investment bankers and corporate attorneys how to drive in the mud and fell trees for firewood in their new state. The narrative begins with acts of nonviolent and almost joy-filled resistance by the accidental activists, which include taking over the airwaves at Starbucks with Radio Free Vermont (“underground, underpowered, and underfoot”) and the rather polite hijacking of a Coors Light truck to replace the cargo with Vermont craft beers (which are mentioned by name in nearly every chapter). It’s like the Vermont Welcome Wagon received training in civil disobedience, with a local brew never far from reach.

It would be presumptuous, from my position of reserve, to make sweeping declarations about what Christianity needs. But I've come to realize what I need from Christianity — a call to action, not permission to engage in the quasi-gnostic pursuit of personal fulfillment.

Pluralism is valuable because Jesus is the sovereign lord of everything — all places, people, religions, and cultures.

EVEN AFTER 200 years, Henry David Thoreau continues to be a controversial (and, to some, annoying) figure. In a 2015 New Yorker article titled “Pond Scum,” Kathryn Schulz eviscerates the 19th century author of Walden, describing him as “self-obsessed: narcissistic, fanatical about self control.”

Schulz is not alone in her criticism. In Thoreau’s own beloved village of Concord, Mass., he was attacked for being a hypocrite because he would slip away from his hand-built cabin in the woods to enjoy hot meals and drop off his laundry at the family home. This after he had brazenly declared himself self-sufficient. To make matters worse, he thundered against alcohol, gluttony, and sex in Walden, just as many were happily putting Puritanism behind them.

Yet Thoreau not only endures but is thriving in today’s 21st century zeitgeist. He has “come down to us in ice, chilled into a misanthrope prickly with spines,” declares Laura Dassow Walls, author of a recently released biography, Henry David Thoreau: A Life.

Walls writes of Thoreau set in a New England deep in the throes of change. Ever mindful of the worrisome new global economy, Thoreau sought out and wrote about those being left out and struggling. His subjects included Native Americans, Irish immigrants, and ex-slaves, who were living precarious lives along Walden Pond. Perhaps his interest stemmed from the fact that, for years, Thoreau’s own extended family lived a life of penury, according to Walls, before the small pencil factory they ran in their backyard prospered, making them comfortable during Thoreau’s adult years.

IMAGINE A gathering of thoughtful American Christians, of diverse backgrounds—from Greek Orthodox to Pentecostal—and each with some experience of the conflict between the Israelis and Palestinians. If you could record their conversations, it might be the beginning of the book that is here before us.

A Land Full of God is an essay collection compiled by Mae Elise Cannon, executive director of Churches for Middle East Peace, to show a range of opinions about the Israel-Palestine conflict in the American church. The writers share a general understanding that peacemaking is the only way forward. Some admit they are exhausted by this conflict. Many express despair over the extremist voices that seem to push the U.S. church around. And a few have suggestions for what might make a difference.

In one of the book’s liveliest essays, Paul Alexander sums up key points: 1) Israel must end its military occupation of the Palestinians and be less violent. 2) Palestinians need to recognize the state of Israel and stop vilifying Jews. 3) Christians need to give a rest to appeals to eschatology in this entire mess. Alexander sounds exasperated and pragmatic, feelings many of us share.

If you’ve had much contact with this topic, it is impossible to read such a book with any neutrality.

TA-NEHISI COATES is an atheist, but in We Were Eight Years in Power he atones for sin. In a 2008 article about Bill Cosby for The Atlantic, Coates failed to thoroughly report on the sexual assault allegations brought against the comedian, only mentioning them briefly. On page 12 of We Were Eight Years in Power, Coates repents. “That was my shame,” he writes. “That was my failure. And that was how this story began.”

By “this story,” Coates means his ongoing career as a correspondent for The Atlantic, during which he has received a MacArthur genius grant, a National Magazine Award, and several other honors for his writings on race in America. Coates is one of the nation’s most popular living chroniclers of the plight of African Americans. But despite that, he is acutely aware of his failings.

We Were Eight Years in Power is both a collection of Coates’ best articles published by The Atlantic and criticism of those pieces. Prefacing most of the articles are short essays by Coates about the stage of life he was in when he wrote each article, the pieces’ triumphs, and their flaws. With sometimes savage specificity, the essays map the evolution of Coates’ writing skills as well as his personal foibles. At the same time, the articles themselves document the flaws of the United States and how the country consistently does wrong by its African-American citizens in favor of doing more than right by its white citizens.

Coates’ writing process is a metaphor for the social corrective he pursues: the abolishment of white supremacy.