women's sexuality

The Sinéad Effect

Nothing Compares documents the tumultuous career of Irish musician Sinéad O’Connor. On live TV in 1992, O’Connor protested child abuse in the Catholic Church, nearly a decade before papal acknowledgment. Her actions jeopardized her career, but she clung to music as a form of healing.

Showtime

In this age of third-wave feminism, many Americans may not realize that Christian women continue to struggle with what many would deem outdated gendered notions. This includes things such as a woman’s calling being second to her husband’s, women as unwitting temptresses who therefore must hide their bodies, and that women may not lead (or sometimes even speak) in church. Both external and internal pressures and fears have historically kept women silent on these matters.

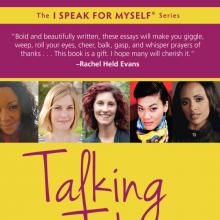

In the recently released Talking Taboo: American Christian Women Get Frank About Faith, 40 women under 40 address head-on many of the taboos remaining at the intersection of faith and gender, and how they are stepping out of historical oppression to make real change within the church.

In her book Lean In, author Sheryl Sandberg notes that while women are outpacing men in colleges and graduate schools, one cannot see this translate to positions of power within corporations. For this imbalance to be righted, Sandberg asserts that women must take charge of their circumstances: “The shift to a more equal world will happen person by person. We move closer to the larger goal of true equality with each woman who leans in.”

This is no less true of women in the church, and leaning in is exactly what the essayists of Talking Taboo are doing.

While Sandberg focuses on issues such as long work hours, daycare, and more flexibility for working moms, the common, though not exclusive, themes of Talking Taboo are sexuality and biblical interpretation.

Most of us are too familiar with this story: an Upper Midwestern Baptist minister claims that “God made Christianity to have a masculine feel [and] ordained for the church a masculine ministry.” Or a Reformed Christian pastor mocks the appointment of the first female head of the Episcopal Church, comparing her to a “fluffy baby bunny rabbit.” Or a Southern Baptist megachurch pastor in California says physical abuse by one’s spouse is not a reason for divorce. Or numerous young evangelical ministers brag about their hot wives in tight leather pants.

Fewer of us are familiar with this story: Tamar is raped by her half-brother Amnon. Tamar protests her brother’s advances, citing the social code of Israel, his reputation, and her shame, to no avail. Their brother Absalom commands her to keep quiet, and their father, the great King David, turns a blind eye.

What do these contemporary statements above, delivered into cultural megaphones with conviction and certainty, have to do with the Old Testament rape and silencing of Tamar? The difficult answer is, quite a lot. The narrative dominance of these stories rests on power and control, which — whether intentional or not — speaks volumes about whom the church serves and what the church values.