Social Justice

Making an ultimatum about church attendance to a sleep-deprived teenager may be my own version of hell on earth.

“We are leaving for church in 10 minutes,” I said, summoning my most authoritative voice before the lifeless lump under the covers.

My seven-year old Annie Sky watched the tense exchange between me and my 14-year old daughter Maya, who made periodic moans from the top bunk. With furrowed brow, my first grader sat on the couch, as if observing a tiebreaker at Wimbledon with no clear victor in sight.

For a moment, I wondered why I had drawn the line in the Sabbath sand, announcing earlier in the week that Maya would have to go to church that Sunday morning after an all-day trip to Dollywood with the middle school band. Somehow I didn’t want Dolly Parton’s amusement park to sabotage our family time in church. (The logic seemed rational at the time).

When Maya lifted the covers, I glimpsed the circles under her eyes and sunburn on her skin. But I repeated my command, with an undertone of panic, since I wasn’t sure if I could uphold the ultimatum.

When she finally got into the car, I breathed deeply and turned to our family balm, the tonic of 104.3 FM with its top 40 songs that we sing in unison. As the drama settled, I realized one reason why I made my teenager go to church: I want my daughters to know that we can recover from yelling at each other (which we had) and disagreeing. We can move on, and a quiet, sacred space is a good place to start.

The television flashes images of a skeletal little girl whose ribs seem to be popping out of her ballooning stomach as she sits in a pile of mud and stares at the camera with large pleading eyes. A “1-800” number flashes on the bottom of the screen. A celebrity does a Public Service Announcement for building wells in Africa. YouTube has sharp pre-packaged videos pulling at our heartstrings, and even months after being released, the KONY 2012 viral video continues to float around the internet.

For Westernized cultures saturated with various forms of media and technologically driven information, social justice is becoming increasingly "packaged," carefully marketed, and commercially manufactured to be a product that incorporates the mission it represents.

Whether social justice organizations should be doing this is debatable. Like everyone else, they’re trying to survive in a capitalistic system that ruthlessly competes for our every dollar. The only problem is that we aren’t the ultimate consumers. For social justice non-profit groups, the sick, poor, starving, abused, and desolate are the true consumers; we’re just the financial and volunteer base needed to keep the system working. To do this, organizations are discovering that a corporate business model is sometimes the only way to survive — and sometimes thrive — within the cutthroat world of advertising and solicitation.

On April 11, 1963 Pope John XXIII published an encyclical some initially dismissed as naive and myopic, as too liberal and too lofty. But today, his "Pacem in Terris" is generally lauded as genius and prophetic – well ahead of its time on the issues of human rights, peace, and equality.

As Maryann Cusimano Love, a Catholic professor of international relations, notes, the same year “Pacem in Terris” was published, spelling out the theological mandate for political and social equality for all people, women in Spain were not allowed to open bank accounts, Nelson Mandela was standing trial for fighting apartheid, and Walter Ciszek was serving time in a Soviet gulag simply for being Catholic.

On Monday and Tuesday, the Catholic Peacebuilding Network hosted a two-day conference at the Catholic University of America, commemorating 50 years since the publication of "Pacem in Terris.”

While everyone was blowing up the Twittersphere decrying the injustices of the Oscars, as movies like Argo walked away with Best Picture honors, I was sitting in a Philadelphia hotel lobby trying to chew on everything I’d heard and seen at this year’s Justice Conference.

The two-day event brought together more than 5,000 people to promote dialogue around justice-related issues, like poverty and human trafficking; featured internationally acclaimed speakers such as Gary Haugen, Shane Claiborne, and Eugene Cho; and exhibited hundreds of humanitarian organizations.

While there is certainly more thinking and processing to be done, here are four things that stood out.

“You’re a Christian? But you’re so nice!”

I’ll never forget these words, spoken to me by a friend of mine from my college’s theatre program. He was one of my more eccentric friends, more blunt than most, and he was also very openly gay. His exclamation of surprise may be the instance that I remember the most, but he certainly wasn’t the only person during my college years to express their surprise at the thought of Christians living by principles of love rather than intolerance, or at the very least, indifference.

I don’t know about you, but I’m pretty sure I have sung “O Little Town of Bethlehem” every year on Christmas Eve for my entire life. But I believe this carol’s lyrics, specifically the words of the first verse, invite a little more thought than we normally give them.

O little town of Bethlehem

How still we see thee lie

Above thy deep and dreamless sleep

The silent stars go by

Yet in thy dark streets shineth

The everlasting light

The hopes and fears of all the years

Are met in Thee tonight

For now let’s ignore the historical inaccuracies of the song, and focus on what the words mean, especially the last four lines. How beautiful is it that through the dark world a light came to bind together the hopes and fears of all the years (I choose to see it as past and future) in Jesus?

I had a conversation with a young woman I met at a conference recently. The conversation rocked me.

I represented the faith voice on a panel at a major secular conference for philanthropists. The panel focused on the question: “What are we not talking about?”

One of my colleagues focused on the nonprofit sector’s inability to make real just change in our world because they are bound by the interests of donors who are, themselves, part of the 1 percent. Another colleague focused on the glut of nonprofits offering similar services in otherwise abandoned communities. I focused on the need for social movements to bring about a more just world and the role of faith communities in those movements, in particular.

As the assistant humanist chaplain at Harvard University, Chris Stedman coordinates its “Values in Action” program. In his recent book, Faitheist: How an Atheist Found Common Ground with the Religious, he tells how he went from a closeted gay evangelical Christian to an “out” atheist, and, eventually, a Humanist.

On the blog NonProphet Status, and now in the book, Stedman calls for atheists and the religious to come together around interfaith work. It is a position that has earned him both strident -- even violent -- condemnation and high praise. Stedman talked with RNS about how and why the religious and atheists should work together.

Some answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What does the term “faitheist” mean? Is it a positive label or a derisive one?

A: It's one of several words used by some atheists to describe other atheists who are seen as too accommodating of religion. But to me, being a faitheist means that I prioritize the pursuit of common ground, and that I’m willing to put “faith” in the idea that religious believers and atheists can and should focus on areas of agreement and work in broad coalitions to advance social justice.

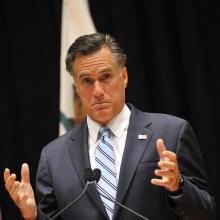

The recently revealed video of Gov. Mitt Romney at a fundraising event last May is changing the election conversation. I hope it does, but at an even deeper level than the responses so far.

There are certainly politics there, some necessary factual corrections, and some very deep ironies. But underneath it all is a fundamental question of what our spiritual obligations to one another and, for me, what Jesus' ethic of how to treat our neighbors means for the common good.

Many are speaking to the political implications of Romney's comments, his response, and what electoral implications all this might have. As a religious leader of a non-profit faith-based organization, I will leave election talk to others.

“In order to serve our world," Bono once said, "we must betray it."

I’ve always wanted to change the world. I’m inspired by stories of people who have left their fingerprints on the very face of culture. I want to be a historymaker. I want to be one who people remember as a person who revolutionized her world.

As noble as this sounds, I’m afraid that up until a few years ago, this has come from a very self-serving motivation. I truly did want to love people and make a difference for their benefit, but I also wanted the credit. Visions of winning a Nobel Prize danced through my mind; dreams of becoming the “woman of the year.” I’ve thought out speeches just in case.

I can’t believe I just admitted that to you. I must really like you.

I had to come to a broken place in order to be ready to bring about the change I so desired to initiate. You see, transformation, no matter how small or big, is never about us. It’s not about the recognition we will receive or about the merit badge that will feed your need for approval. No, it’s the most selfless thing we will ever do. We need to be trustworthy to lead such efforts.

All it takes is a heart that truly cares for others — that’s it. Once your eyes are off yourself, you become incredibly useful! What a thrill it is to add benefit to others and get no credit for it.

On Aug. 17, three members of the Russian feminist punk band/performance art group Pussy Riot received the verdict in the criminal case against them: Guilty of "hooliganism" motivated by "religious hatred." Each was sentenced to two years in prison.

As a faith-based community organizer, I spend a great majority of my time trying to get political issues into the church so that the gospel can be relevant to the reality of those on and off the pews.

Therefore, I believe the best place for a “pussy riot” is the church. Although this may seem sacrilegious, here's why:

1. When the church ignores social and political issues it silently blesses injustice. (See slavery, the Holocaust, lynching, and child sexual abuse.) Testimony Time is a set time in many Black Churches when congregants can speak of their pains and triumphs and how God brought them through.

Testimony time is democratic and a time of raw honesty. I call what Pussy Riot did protestifying because they protested by testifying about the political conditions of their country.

Near the turn of the 2nd century A.D., the poet Juvenal published a collection of verses titled Satires. Among other things, the text was intended to spark discussion about social norms at a time when the masses were increasingly withdrawn from civil engagement.

In specifics, Juvenal wrote:

…everything now restrains itself and anxiously hopes for just two things: bread and circuses.

According to Juvenal, the public of his day and age was growing less concerned about social responsibility due to personal pursuits of bread (comfort) and circus (entertainment). In addition, he believed political leaders used the distribution of comfort and entertainment as a way to sedate the population, distract them, and open opportunities for systemic manipulation.

Juvenal believed far too many citizens were far too willing to cooperate in their own exploitation.

What I find incredibly intriguing — and disconcerting — about Juvenal’s observations is that, numerous generations later, it can be argued that much of what he considered to be problematic in his era can now be found in North America.

On Friday, The New York Times reported:

"Moshe Silman, the desperately indebted Haifa man who set himself aflame last weekend as part of a social justice protest in Tel Aviv, died Friday from the second- and third-degree burns over 94 percent of his body.

In the year since 400,000 people filled Tel Aviv’s Rothschild Boulevard last summer, setting off a national protest movement, Mr. Silman, 57, had become a fixture of demonstrations in Haifa. His self-immolation stunned but also galvanized the protest movement, which had been struggling to find its footing."

Learn more here

It’s July 5 and we’ve got a little gift for you all.

The Sojourners office is only occupied today by a motley crew of staff who fall into two categories: those who were smart enough to not end up with any medical emergencies due to improper use of home fireworks, and those of us who weren’t smart enough to use the July 4th holiday as an opportunity for a five-day weekend. But, with this small, slightly dim group with highly refined survival instincts, we are still ready to bring you some great content.

We work hard every day to make sure our God's Politics blog brings you news and commentary on issues important to Christians who care about social justice. Still, it always seems like there is way more going on all day, every day than one person can ever keep up with.

For all of you who are unlucky enough to be chained to a computer, Blackberry (does anyone still use these?) smart-phone or are otherwise more electronically connected then you would like to be—we’ve got a special treat: our newest blog, “Quick Read: Social. Justice. News."

“TAMARA” GREW UP in an affluent, middle-to-upper-class neighborhood. Her friends, including the ones she knew from church, were her cousins, neighbors, and other kids who were a lot like her. Her parents worked hard at building a “safe zone” to protect her from harm—but, as Tamara looks back on her childhood, she can see the lasting fear that it instilled in her.

After she got her driver’s license, she always double-checked that her car doors were locked as soon as she was in the vehicle, and she avoided her city’s small downtown area. To this day, she detests large cities and is constantly worried that someone will rob her. Tamara suffers from “mean world” syndrome: a hyper-vigilant state in which strangers are to be ignored and avoided, new experiences are to be feared, and other people’s problems are just that. It’s a survival mode based on scarcity, hoarding, looking out for number one. Too often, it involves shrinking back from active involvement in the biblical call to social justice.

Sadly, many parents put children in a kind of quarantine—not seeking justice, but fearing contamination. The view that children are pure and the world is corrupt has led well-intentioned adults to (over)protect children from poverty, disease, violence, and other “pollutants.” (Of course, this isn’t to say that all children grow up sheltered; many experience situations of poverty, violence, and oppression that sheltered families can’t even imagine.) Ironically, as children are quarantined from the harmful realities of the world, they’re often exposed to virtual violence through television, music, and video games. This is a recipe for creating kids who, like Tamara, are afraid of the unknown that exists beyond their bubble-wrapped microcosms.

How do you get your kid to care about social justice? Well, you can bring her to marches and protests on important issues before she’s old enough to walk; croon her to sleep with freedom songs; or fill her Christmas stocking with fair-trade goodies.

My parents did all that when I was little. Some of my earliest memories involve talking to homeless people in my neighborhood, attending demonstrations with my church, door-to-door lobbying with my mom, even dressing up as Winnie the Pooh on a couple occasions to raise awareness about corporate child labor practices. But these events were just the side effects of having activist Christian parents; they say little about our family life and my own formation as a young person.

Perhaps one of the keys to social justice parenting is to ignore the question above. You can’t get your kid to care about social justice issues. Much like you can’t force your child to be a Christian, to dress a certain way, or to listen to certain music, you can’t set out with a goal to shape your child’s passions and interests. Parents who do this either get lucky or, more likely, meet strong resistance from their young ones. My father tells me that the question parents should continuously ask themselves is this: How can I reflect a vision for a more just and compassionate society within my family?

The goal of social justice parenting is not to produce the “right” kind of child—it is to create an environment in which love flourishes and the structures of family life are consistent with a vision for a better world. In my family, this meant that we functioned democratically (or, to my 4-year-old mind, with everyone “on board”). For the most part, we made decisions at weekly family meetings in which everyone had an equal opportunity to participate. My parents tried not to use age, education level, and income as trump cards for important family matters. That is, we rarely heard the phrases: “Because I said so,” or, “Because I know more than you do,” or “Because it’s my money.”

AFTER THE VATICAN’S “hostile takeover” of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious in April, I was particularly struck by one joke I encountered: “Go Catholic ... and leave the thinking to us.”

I laughed—but not much. That one, it seems, is too close to the truth these days.

The Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR), a major educational center for superiors of Catholic women’s religious orders in the U.S., was launched in 1956 at the urging of the Vatican. For years, it has been a venue where officers of every congregation of women religious are invited to meet, study, and consider together the role and place of women religious in the resolution of the issues of the time. Now the LCWR has been put under the control of three bishops: Peter Sartain of Seattle; Leonard Blair of Toledo, Ohio; and Thomas John Paprocki of Springfield, Illinois.

The officers and body of the LCWR—all superiors, prioresses, or other officials of major, longstanding institutions—are no longer authorized to plan its programs, engage its speakers, or create and implement its structures. Instead, Sartain, Blair, and Paprocki have been appointed to oversee the group: to approve its programs, create its constitutions, determine its operational procedures, and define the content of its conferences. As in, “Leave the thinking to us.”

As in, women can’t do it themselves. Or, women aren’t moral agents. Or, women don’t know what they’re doing. Or, the girls need to be controlled. Or, father knows best.

The better way says, if we follow God’s religious values we can use global technology, green economy, and targeted economic and infrastructure investment, total access to education, and creative job creation strategies to address the ugly realities of poverty. If we follow the enduring ethic of love we can beat our swords of racism into the plows that will till the new soil of brotherhood and sisterhood

If we see the poor as our neighbors, if we remember we are our brother’s keeper, then we shall put the poor, rather than the wealthy, at the center of our agenda.

If we hold on to God’s values, the sick shall have good health care. The environment shall be protected. The injustices of our judicial systems shall be made just. We shall respect the dignity of all people. We can love all people. We can see all people as God’s creations.

We can use our resources to develop our minds and economy, rather than build bombs, missiles, and weapons of human destruction.

Do we want to keep pressing toward God’s vision? Values are once again the question of our times.

Do we want a just, wholesome society, or do we want to go backwards? This is the question before us. And I believe that at this festival there is still somebody who wants what God wants. Somebody who understands there are some things with God that never change

There are still some prophetic people that have not bowed, who as a matter of faith know that Love is better than hate. Hope is better than despair. Community is better than division.

Peace is better than war. Good of the whole is better than whims of a few. God wants everybody — red, yellow, black, brown and white taken care of. God wants true community, more togetherness … not more separateness. God wants justice, always has, always will.

Because with God some things never change.