Questions

Florida is a target state for traffickers, with the Tampa Bay area as a top destination for this monstrous activity. Tampa Bay has a lethal combination of tourism, world famous beaches, hospitality and agricultural industries, sports arenas, a military base, international seaports and airports, as well as a destination spot for one of thelargest adult entertainment industries in the nation. This combination attracts all forms of human trafficking which has become a larger money maker than selling drugs, as the human "product" can be used and re-used over and over again.

IT’S A TRUISM to say that television is outpacing cinema for entertainment quality and depth of exploration. Since The Wire appeared a decade ago, studios have been realizing that there is an audience for long-form storytelling that is willing to think.

Recently I’ve been struck by the set-in-the-’80s espionage thriller The Americans, the deeply haunting police procedural True Detective, the hilarious pathos of Louie and Veep, and the sly, shocking Hannibal, a prequel to The Silence of the Lambs: All hugely entertaining, dramatically credible, and challenging both as works that require sustained attention and in terms of what they say about life. The Americans is really an exploration of marriage and cultural identity wrapped up in Cold War cloaks-and-daggers; True Detective is a lament for the broken parts of America, and an affirmation that friendship endures above almost everything else; and Hannibal is a postmodern delving into Dante’s Inferno, looking at the underbelly of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s assertion that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

What’s most exciting is that it’s now considered viable to make drama that actually asks real questions about life and is prepared not to answer them pat. Along with the vast amount of social media conversation about these works, what we have is more akin to ancient forms of public entertainment that required a kind of audience participation—theatrical catharsis meeting gathered conversation to produce a community hermeneutic. When we talk about TV and cinema, we’re talking about ourselves.

MY 5-YEAR-OLD daughter, Zoe, is in preschool. This means, as most parents of school-age children know, that there is a birthday party to attend approximately every other weekend of the year.

On the way to one of these myriad celebrations, we stopped by the church in downtown Portland, Ore., where my wife, Amy, is the senior pastor. She had a daylong meeting, and we needed to switch cars, as hers was the one with the gift in it.

As we came down the front steps of the church and onto the South Park Blocks, a local city park, we saw at least half a dozen emergency vehicles parked in a haphazard formation along the street and on the sidewalk in front of a small public restroom. Several officers were standing together, making calls on their radios and discussing the situation at hand. At their feet was what appeared to be a lifeless body, lying on the pavement underneath a blue tarp.

“Daddy,” Zoe said, “what are those police mans doing in the park?”

“I’m not sure, honey,” I said, “but it looks like somebody needed their help.”

“Is somebody in trouble?”

“Something like that,” I sighed. “Make sure you don’t drag that gift bag on the ground. We don’t want to mess up your friend’s present before we get to the party.”

My first thought was, God, please don’t let it be Michael. Michael is a man about my age who lives outside and wrestles daily with an addiction to alcohol, among several other things. We have helped him get sober, only to see him relapse. We helped him get into supportive housing, only to watch him get into a fight and get thrown back out onto the street.

Prophets are always asking questions. Tough questions. Unsettling questions. Questions that they pose to themselves, then try to answer by how they live.

Questions such as:

What’s in our hearts? Are we concerned too much about ourselves and too little about others? Do we believe in love? Why do we give in so readily to bitterness and hatred?

Why do so few have so much, while so many have so little? Aren’t we all diminished by the poverty, discrimination, violence, and the various injustices in our world? Why do we glamorize violence and weapons as solutions to our problems?

In a world where people are craving inspiration, growth, and information, many churches maintain a cyclical pattern based on redundancy, safety, and closed-mindedness. Unfortunately, many pastors and Christian leaders continue to recycle old spiritual clichés — and sermons — communicating scripture as if it were propaganda instead of life-changing news, and driving away a growing segment of people who find churches ignorant, intolerant, absurd, and irrelevant.

As technology continues to make news and data more accessible, pastors are often failing to realize that they're no longer portrayed as the respected platforms of spiritual authority that they once were.

Instead of embracing dialogue and discussion, many Christian leaders react to this power shift by creating defensive and authoritarian pedestals, where they self-rule and inflict punishment on anyone who disagrees, especially intellectuals.

SALT LAKE CITY — It is wrong to assume that Mormons who leave the faith “have been offended or lazy or sinful,” a top leader told members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on Saturday during the church’s 183rd Semiannual General Conference.

“It is not that simple,” said Dieter F. Uchtdorf, second counselor in the LDS Church’s governing three-man First Presidency.

Some struggle with “unanswered questions about things that have been done or said in the past,” Uchtdorf explained. “We openly acknowledge that in nearly 200 years of church history — along with an uninterrupted line of inspired, honorable and divine events — there have been some things said and done that could cause people to question.”

During the Christian spiritual journey, followers of Christ are forced to eventually face some basic faith-related questions. Here are a few of the most common ones:

1) What is salvation?

What does salvation really mean? When does it happen and is it permanent? Do you choose your own salvation or is it predestined? Is everyone saved or just a select few?

The idea of salvation is extremely complex, and our concept of it directly influences how we live, evangelize, and interact with the people around us.

JUST A FEW dozen pages into Faith, Doubt, and Other Lines I've Crossed, evangelical pastor Jay Bakker pens what may be the best explanation for the Christian emphasis on church community that I've ever encountered. Noting that doubt can be "hard and scary," Bakker writes: "That's why we have one another, why we have community. We can go through those days of doubt together. I wouldn't be who I am today if it weren't for the people who have been there with me as I question everything."

Many writers have grappled with the challenge that doubt poses for religious believers. But in this honest, searching, and ultimately uplifting book, Bakker pulls doubt out of the shadows where many believers wrestle with it on their own and instead presents it as a reality that Christian communities can and should address together.

Bakker's approach to the often-taboo topic of questioning—or, as he puts it, "the sense that faith is crap, life is meaningless, there is no God, the Bible is a fraud, Jesus was just a charismatic man turned mythological figure if he existed at all"—is shaped by his childhood in a Pentecostal environment that left no room for doubt. As Bakker ruefully notes in the book's introduction, "I will probably be 80 years old and still introduced as Jay Bakker, son of Jim and Tammy Faye." That unusual background only provides the impetus, however, and not the substance for this book, which reads mostly as the stream-of-consciousness meditation of a man pushing and pulling at his faith to see if it holds up.

I’ve seen plenty of articles responding to the shooting in Sandy Hook, Connecticut. Some are angry, some pastoral, still others, prophetic in their call for change in various forms. I have little to add to the conversation at that level, but I have heard questions from many children, some from my own kids. I thought I’d offer some responses I’ve shared.

What happened?

Something terribly sad. A man hurt some children and adults in a school in Connecticut. Some of them died. The teachers and students were very brave, and the community is working together to take care of those who survived and those who lost someone they loved. Even the President went there to be with them.

Everyone who calls me to speak somewhere, it seems, wants me to address the issue of declining church membership, and particularly how to connect with younger adults. The problem is that sometimes the invitation is built on a false premise. It’s the hope of many churches that if they can find a way to connect with younger people in a relevant way, those young adults will join the church and save the institution for future generations.

And while this is possible in some situations, it’s really the wrong question to be asking.

The explicit question I get asked, time and again, is “How do we better serve younger people?” And if the question really ended there, we could have a pretty productive conversation. But there’s an implied subtext in most cases that we have to tease out, and often times, the church isn’t even willing to admit that this footnote is married to their question. So although the words above are what are spoken, here’s what they really want to know:

“How do we better serve younger people (so that they will come back to our institutions and save them)?”

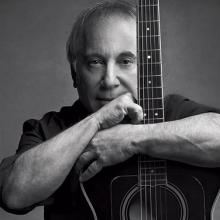

"How was all of this created? If the answer to that question is God created everything, there was a creator, than I say, great! What a great job. And I like the idea. I find it very, I don’t know, I find it comforting in some way. But if the answer to that is there is no God, I don’t feel like, well, what a jerk I’ve been. I feel, oh fine, so there’s another answer. I don’t know the answer. I’m just a speck of dust here for a nanosecond, and I’m very grateful." — Paul Simon in an interview that will air this weekend on the PBS program Religion & Ethics Newsweekly.

Watch the interview in its entirety inside ...

Your magazine just brought me to tears. I was standing in front of the magazine display in the library of Montrose, Colorado, when I happened to see your latest issue.