Pentecostalism

THE PASSION CENTER is a Christian community in Pembroke Pines, Fla., about 20 miles north of Miami. The organization is affiliated with the Assemblies of God, a Pentecostal denomination, but it neither emphasizes its denominational ties nor resembles a traditional church. This self-described “holistic ministry training center” has no building, but it has a mission to keep Jesus and social justice intertwined.

The faith community was founded and is led by Elizabeth Rios, who earlier started the Center for Emerging Female Leadership in New York. Members of the Passion Center used to meet regularly for community service projects, local demonstrations advocating for the priorities of marginalized communities, dinners in local restaurants, and a monthly comedy night for their neighborhood. The pandemic shut down the in-person gatherings. Unlike many other Pentecostal and charismatic churches, the Passion Center leadership had no qualms about following the science. They had no building to close; they just transitioned their ministries online. The Passion Center is one example of Pentecostals who don’t mind getting politically engaged in justice work to further the reign of God here on earth.

Pentecostalism is one of the fastest growing Christian movements in the world. In 1980, about 6 percent of Christians globally were Pentecostal—now it’s 25 percent. As of 2014, there were 10 million Pentecostals in the U.S. In many places around the world, Pentecostalism is the predominant face of Christianity. These rising numbers are shifting Christianity’s demographic center from the prosperous North to the global South.

Ariyo Olasunkanmi / Shutterstock.com

IN 1906, a few hundred people were present at Azusa Street Mission revivals in Los Angeles, which are regarded as the beginning of modern Pentecostalism. A century later, Pentecostal/Charismatic Christianity claims about half a billion adherents worldwide.

Around the world, where work for change is happening, it’s often Pentecostals in the middle of it.

For example, Donald E. Miller and Tetsunao Yamamori, two scholars based at the University of Southern California, examined flourishing churches in the global South that were involved in social issues (churches that were indigenous to their areas—that is, not reliant on foreign resources). To the surprise of Miller and Yamamori, authors of Global Pentecostalism: The New Face of Christian Social Engagement, 85 percent of them were Pentecostal and Charismatic churches.

What motivates these churches to roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty in serving their neighbors? Is it poor economic conditions? If the answer is related to context, why are these Pentecostal churches more engaged and proactive than their Catholic or Protestant counterparts?

There are several key Pentecostal beliefs that encourage response to social challenges:

1) Called: God touches us!

The Pentecostal movement is best characterized by personal experiences with God. Often supernatural in nature, these encounters with God are described as “crisis experiences,” and they tend to revolutionize the believer’s faith, attitude, behavior, and life.

For example, the Yoido Full Gospel Church in Korea publishes Shinang-gye (World of Faith), a popular monthly magazine that features testimonies of divine healings and miracles. Such testimonies affect others and reinforce a key value among Pentecostals: Most human problems are spiritual at their core.

This assumption has significant implications. First, in Pentecostal worship such an encounter with God is expected, encouraged, and facilitated. Songs, preaching, prayer, altar call, and other components of Pentecostal worship lead worshippers to enter into a “holy ground” where one meets the loving and powerful God. This makes Pentecostal worship dynamic and vibrant.

The same week that President Donald Trump was meeting with Pope Francis in Rome, another historic event was taking place, as the Global Christian Forum facilitated a groundbreaking encounter with the major global bodies representing most every part of world Christianity.

Most often Pentecost comes to us as a momentous Christian occasion of spiritual power, ethnic unity, gender equality, multi-generational comradery, and immigrant hospitality. But when the moment has passed, it gives way to the more ignoble features of life and community, like spiritual apathy, sexism, racial prejudice, ageism, xenophobia, etc.

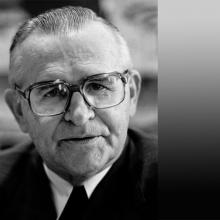

Brazilian Cardinal Paulo Evaristo Arns, one of the most important figures in modern Brazil, died on Dec. 14 in Sao Paulo. He was 95.

Known as Dom Paulo, he was appointed bishop in 1966 and served as archbishop of the Sao Paulo Archdiocese from 1970 to 1998. But he was better known as the “people’s bishop,” and embodied the progressive church movement in South America.

Image via Roberto Rodriguez / St. Louis Post-Dispatch / RNS

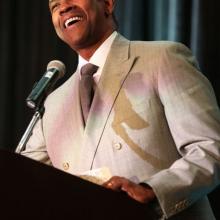

Hollywood star Denzel Washington, the son of a pastor, preached a sermon of gratefulness Nov. 7 to hundreds of members of the Church of God in Christ at their annual Holy Congregation in downtown St. Louis.

“I pray that you put your slippers way under your bed at night, so that when you wake in the morning you have to start on your knees to find them. And while you’re down there, say thank you,” he told the crowd at a $200-a-plate banquet at the Marriott St. Louis Grand Hotel to raise money for the denomination’s charity work.

“It is impossible to be grateful and hateful at the same time,” he said.

“We have to have an attitude of gratitude.”

“It’s a new form of Christianity,” explained Opoku Onyinah, “now also living in the West.” He’s the president of the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council, and also heads the Church of Pentecost, begun in Ghana and now in 84 nations. Onyinah was speaking at a workshop on “How Shall We Walk Between Cultures,” and explaining how African Christianity is interacting with postmodern culture. It was part of Empowered21, which gathered thousands of Pentecostals in Jerusalem over Pentecost.

I’ve found this idea intriguing. Pentecostalism, especially as it is emerging in the non-Western world, is a postmodern faith. Often I’ve said, “An evangelical wants to know what you believe, while a Pentecostal wants to hear your spiritual story.” Perhaps it’s an oversimplification. But Pentecostalism embodies a strong emphasis on narrative and finds reality in spiritual experiences that defy the logic and rationality of modern Western culture.

Christine Caine gave a passionate and prophetic call for the church to be continually changing, even while at its core, it is “the same.” That constant change is driven by God’s continuing call to be sent as witnesses in the world. “We want power,” she told the spiritually hungry Pentecostals gathered before her. “But we don’t know what it’s for.” It’s not for ourselves, not for our own spiritual ecstasy. The power of God’s Spirit is given for us to be witnesses to God’s transforming love. And one can’t change the world without being in the world, instead of running from it. “We’re not here,” Christine Caine proclaimed, “to entertain ourselves.”

You could feel how her words stuck a deep chord within the crowd of those listening. I walked over to sit by a friend who is bishop of a large Pentecostal church. “This is the best word that’s been spoken,” he said to me. And that’s after we had heard eight world famous Pentecostal preachers.

JERUSALEM — One out of four Christians today is Pentecostal or charismatic, which means one of every 12 persons living today practices a Pentecostal form of Christian faith. This, along with the astonishing growth of Christianity in Africa, are the two dominant narratives shaping world Christianity today. Further, the gulf between the older, historic churches, located largely in the global North, and the younger, emerging churches in the global South, often fueled by Pentecostal fire, constitutes the most serious division in the worldwide Body of Christ today.

One can also frame this as the divide between the global Pentecostal community, and the worldwide ecumenical movement. Each lives in virtual isolation from the other, and both suffer as a result. I call it ecclesiological apartheid, with its own endless, winding walls of separation. And these walls need to come down, for the sake of God’s love for the world.

It’s become my passion, in whatever small ways, to make some cracks in these walls.

The story of world Christianity’s recent pilgrimage is dramatic and historically unprecedented. The “center of gravity” of Christianity’s presence in the world rested comfortably in Europe for centuries. In 1500, 95 percent of all Christians were in that region, and four centuries later, in 1910, 80 percent of all Christians were in Europe or North America.

But then, world Christianity began the most dramatic geographical shift in its history, moving rapidly toward the global South, and then also toward the East. By 1980, for the first time in 1,000 years, more Christians were found in the global South than the North. Growth in Africa was and remains incredible, with one of our four Christians now an African, and moving toward 40 percent of world Christianity by 2025. Asia’s Christian population, now at 350 million, will grow to 460 million by that same time. Even today, it’s estimated that more Christians worship on any given Sunday in churches in China than in the U.S.

High-octane contemporary worship with smoke, flashing lights, and words on huge screens energize and empower 3,400 Pentecostals from 69 countries filling the Calvary Convention Centre in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia,. This is the 23rd Pentecostal World Conference, a triennial gathering of pastors, leaders, and youth from around the globe. I’m here as part of a delegation from the Global Christian Forum, warmly invited, seated right in the front, and including representatives from the Lutheran, Orthodox, Seventh-Day Adventist, Mennonite, African-Instituted and Reformed church bodies, all members of the GCF steering committee. We’re easy to pick out of the crowd, since we’re the only ones who don’t spontaneously raise our hands in worship. I hope that image doesn’t make it to the big screens.

The explosive growth of Pentecostalism is an astonishing chapter in the story of world Christianity’s modern history. In 1970, Pentecostals (including charismatics in non-Pentecostal denominations) totaled about 62 million, or 5 percent of the total Christian population. In the four decades since, Pentecostals have grown at 4 times the rate of overall Christianity, and 4 times faster than the world’s population growth. Today they number about 600 million — one out of every four Christians in the world, and one out of every 12 people alive today. Most of this growth has come in the global South, in places like Africa, South America, and — yes — Malaysia.

The Pentecostal World Conference doesn’t look much like a typical denominational or ecumenical assembly. It’s more like a global revival service. Several of the world’s best-known Pentecostal preachers and leaders deliver stirring messages, complete with altar calls for those seeking the fresh empowerment of God’s Spirit in their lives and ministries. It’s a far cry from a Reformed Church in America General Synod, which I facilitated for many years. But these keynote speakers, along with the workshops held each day of the conference, open a window into global Pentecostalism’s present trends, challenges, and directions.

In writing From Times Square to Timbuktu: The Post-Christian West Meets the Non-Western Church, I found that one of the most intriguing questions I encountered is how rapidly growing forms of Christianity in the global South deal with social and economic issues within their societies. So in Kuala Lumpur, I was especially attentive to what might be said by the world’s Pentecostal leadership about the biblical call to justice and mercy. And I heard a lot that I wish I could now go back and add to my book.

The atlas also documents other dramatic trends, including the fragmentation of Christianity. New denominations, often borne out of strife and division, multiply endlessly. In Korea, for instance, there are now 69 different Presbyterian denominations. At the rate we are going, by 2025 there will be 55,000 separate denominations in the world!

That is an utter mess fueled by rivalry and confusion that hampers the church's witness and makes a mockery of God's call to live as parts of one body.

The atlas also documents the dramatic rise of revival movements throughout the world, and charts the story of Pentecostalism's rise. From its beginning a century ago, Pentecostalism now comprises a quarter of all Christians in the world. This fundamental change in Christianity's global composition, along with its geographical transformation, has created a dramatically different Christian footprint in the world.

The puzzle here is not that readers of the Bible would tilt toward the political left. That, for me, as well as for thousands of other American evangelicals, is self-evident. Jesus, after all, summoned his followers to be peacemakers, to turn the other cheek, to welcome the stranger and to care for “the least of these.” He also expressed concern for the tiniest sparrow, a sentiment that should find some resonance in our environmental policies.

The puzzle here is not that readers of the Bible would tilt toward the political left. That, for me, as well as for thousands of other American evangelicals, is self-evident. Jesus, after all, summoned his followers to be peacemakers, to turn the other cheek, to welcome the stranger and to care for “the least of these.” He also expressed concern for the tiniest sparrow, a sentiment that should find some resonance in our environmental policies.

No, the real conundrum lies in the subtitle the editors of Christianity Today assigned to Franzen’s article, which was titled, “A Left-Leaning Text.” Adjacent to a picture of a Bible tilted about 45 degrees to the left, the editors added the subtitle: “Survey Surprise: Frequent Bible reading can turn you liberal (in some ways).”

The fact that anyone should register surprise that the Bible points toward the left should be the biggest surprise of all.

As Christianity explodes across the globe, it is taking new forms and moving away from traditional expressions.

At the Faithdome in South Central Los Angeles in May, one of the most dynamic religious movements in the world was out in full force...

Like many North American Christians, I had my spiritual journey upended in the 1980s by an encounter with poor believers from Latin America.

I heard it in passing on National Public Radio’s All Things Considered one afternoon; it was a blurb for an upcoming story.

With hoots and hollers, the pentecostal 'Toronto Blessing' invites us to celebrate a love affair of faith. But what's missing from this party?