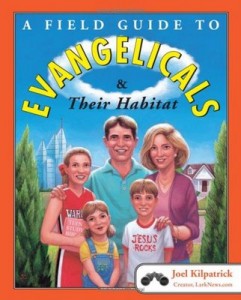

american evangelicals

Because of evangelical political behavior over the last several decades, it’s tempting to believe that evangelicals have always supported right-wing causes and politicians. That is not the case, and there’s some reason to believe that in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election, we may be witnessing an awakening of conscience among some evangelicals. If so, progressive evangelicals could do far worse than look to the 1970s for inspiration.

An acquaintance of mine on Facebook recently posted something different than her usual scripture verses. She shared a petition asking Florida to stop mandatory shelter-in-place orders. “It’s not that I don’t want people healthy, it’s that I don’t want my freedom taken from me,” she wrote.

WHAT VALUES WERE really at stake for the 81 percent of white evangelicals who voted for a presidential candidate who uses crass language and admits to engaging in coarse behavior, and whose campaign was marked by vitriolic hatred of various people, particularly people of color?

I raised this question with a white male leader of a Christian foundation. In response, he told me to consider the “moral values”—such as pro-life concerns—that he said prompted, if not demanded, white evangelical support of Donald Trump’s candidacy.

The Christian leader suggested that these particular concerns mitigated any misgivings that white evangelicals might have with Trump’s dissolute behaviors and bigoted views. For many others, the moral imperatives not to support Trump were more overriding, especially for those who prioritize personal virtue as a core religious value.

The “value proposition” displayed by white evangelicals in the 2016 election, and the definition of what constitutes “moral values” and what doesn’t, is inextricably related to the nation’s upcoming demographic shift—the fact that, by the year 2044, the United States is expected to become majority nonwhite. This has significant implications for the wider faith community regarding issues of race. Much more may be at stake than the leader of the Christian foundation was able or willing to recognize.

‘The new Israelites’

The value proposition of the Trump campaign was made clear in the campaign’s “Make America Great Again” vision. This mantra tapped into America’s defining Anglo-Saxon myth and revitalized the culture of white supremacy constructed to protect it.

The Anglo-Saxon myth was introduced to this country when America’s Pilgrim and Puritan forebears fled England, intent on carrying forth an Anglo-Saxon legacy they believed was compromised in English church and society with the Norman Conquest in 1066. These early Americans believed themselves descendants of an ancient Anglo-Saxon people, “free from the taint of intermarriages,” who uniquely possessed high moral values and an “instinctive love for freedom.”

Trump’s trip, then, is the epitome of this unique, sales-based approach that characterized his campaign and administration — a move toward achieving personal, political, and even religious victory, simultaneously. But to what end? The only clear motivation to which I can point is the uncannily vague promise to “Make America Great Again.”

(RNS) Dozens of conservative evangelicals and Catholics have signed an open letter urging their progressive counterparts to “repent of their work that often advances a destructive liberal political agenda.”

The letter, posted online six weeks before Election Day by an alliance called the American Association of Evangelicals, includes criticism of Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

I occupy a strange place between cultures. Not the international cultures of my childhood spent as a missionary kid living around the world, but between two sub-cultures here in modern America. I am a rare breed of evangelical that doesn’t live in a bubble of Christian culture. Quite the opposite. I live and work in higher education, and — mark it — secular higher ed.

An evangelical acquaintance once asked me delicately, “Is there a reason you and your husband don’t work at a Christian university?”

I could hear the gears in his head as he tried to reconcile what he saw before him: two highly educated, devout Christians working in the "liberal bastion" of a secular college. Why on earth would we do such a thing to ourselves?

The truth is, Dwayne and I live and thrive in the place we’ve carved out outside the bubble of American evangelicalism. It’s not that we don’t love the evangelical church, or don’t attend an evangelical congregation.

It’s just that we don’t identify with all aspects of the American version of evangelicalism.

He and I both came to know Jesus outside the States. We are both missionary kids. In addition, Dwayne is Canadian. As a result, we have an outsider’s perspective. For us, living in America and being evangelical poses an interesting paradox.

In so many ways, living and working with people who have vastly different life experiences than our own feels normal. After all, that’s how we grew up — in the company of friends whose worldviews are shaped by the submerged iceberg of cultures not our own. These differences don’t threaten our beliefs. Ironically, holding the space for the lived experiences of our friends creates an environment that also affirms our lived experiences, and more importantly, our faith.

On Feb. 21, Time.com broke the news that my evangelical publisher, Destiny Image, dropped a book contract it had made with me almost a year ago because its buyers refused to sell my book due to my pro-LGBTQ activism.

Many conservative evangelicals have called my pro-LGBTQ stance “deplorable” and labeled me a false teacher. Other progressives have uplifted my story as one that demonstrates the discrimination that too many conservative Christians have become known for. In all of this coverage, both positive and negative, though, the true message of my situation has gotten lost.

Sure, my publisher dropped my book contract. Sure, evangelical booksellers seem to have blacklisted me and refuse to sell my evangelical book in evangelical bookstores — a too-close-to-home example of the evangelical discrimination against the LGBTQ community and our allies.

But at the heart of this controversy, there’s a deeper problem: a fundamentally flawed belief that one cannot be a true Christian if one identifies as LGBTQ (or an ally of LGBTQ people).

Tonight, Sojourners and the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission are co-sponsoring an event to discuss religion and the 2012 elections. Rev. Wallis and Dr. Richard Land will delve into what they believe the religious issues will be and should be from now until election day.

The event is already turning some heads. A Washington Post article by Michelle Boorstein summed up the unique nature of the event in a headline, "Evangelical opposites to hold discussion on 2012 presidential race."

The puzzle here is not that readers of the Bible would tilt toward the political left. That, for me, as well as for thousands of other American evangelicals, is self-evident. Jesus, after all, summoned his followers to be peacemakers, to turn the other cheek, to welcome the stranger and to care for “the least of these.” He also expressed concern for the tiniest sparrow, a sentiment that should find some resonance in our environmental policies.

The puzzle here is not that readers of the Bible would tilt toward the political left. That, for me, as well as for thousands of other American evangelicals, is self-evident. Jesus, after all, summoned his followers to be peacemakers, to turn the other cheek, to welcome the stranger and to care for “the least of these.” He also expressed concern for the tiniest sparrow, a sentiment that should find some resonance in our environmental policies.

No, the real conundrum lies in the subtitle the editors of Christianity Today assigned to Franzen’s article, which was titled, “A Left-Leaning Text.” Adjacent to a picture of a Bible tilted about 45 degrees to the left, the editors added the subtitle: “Survey Surprise: Frequent Bible reading can turn you liberal (in some ways).”

The fact that anyone should register surprise that the Bible points toward the left should be the biggest surprise of all.

Most of my friends knew evangelicalism only through the big, bellicose voices of TV preachers and religio-political activists such as Pat Robertson, the late Jerry Falwell and James Dobson. Not surprisingly, my friends hadn't experienced an evangelicalism that sounded particularly loving, accepting or open-minded.

Most of my friends knew evangelicalism only through the big, bellicose voices of TV preachers and religio-political activists such as Pat Robertson, the late Jerry Falwell and James Dobson. Not surprisingly, my friends hadn't experienced an evangelicalism that sounded particularly loving, accepting or open-minded.

After eschewing the descriptor because I hadn't wanted to be associated with a faith tradition known more for harsh judgmentalism and fearmongering than the revolutionary love and freedom that Jesus taught, I began publicly referring to myself again as an evangelical. By speaking up, I hoped I might help reclaim "evangelical" for what it is supposed to mean.

A week or two after the 2004 election, I was dining with some friends in New York when the conversation turned to religion and politics -- the two things that you're never supposed to discuss in polite company.

George W. Bush had just been re-elected with the help of what was described in the media as "evangelical voters." And knowing that I am an evangelical Christian, my friends were terribly curious.

"What, exactly, is an evangelical?" one gentleman asked, as if he were inquiring about my time living among the lowland gorillas of Cameroon.

I suddenly found myself as cultural translator for the evangelical mind.

"As I understand it," I began, "what 'evangelical' really means is that a person believes in Jesus Christ, has a personal relationship with him and because of that relationship feels compelled to share their experience of God's love with other people. "How they choose to share that 'good news' with others is entirely up to the individual. Beyond that, the rest is details and style."